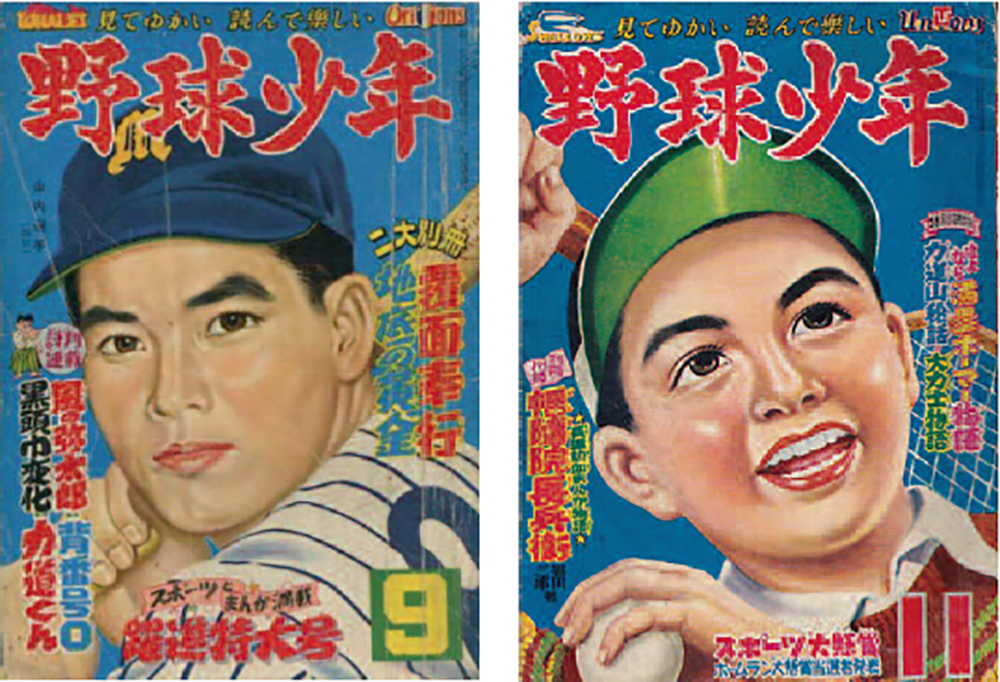

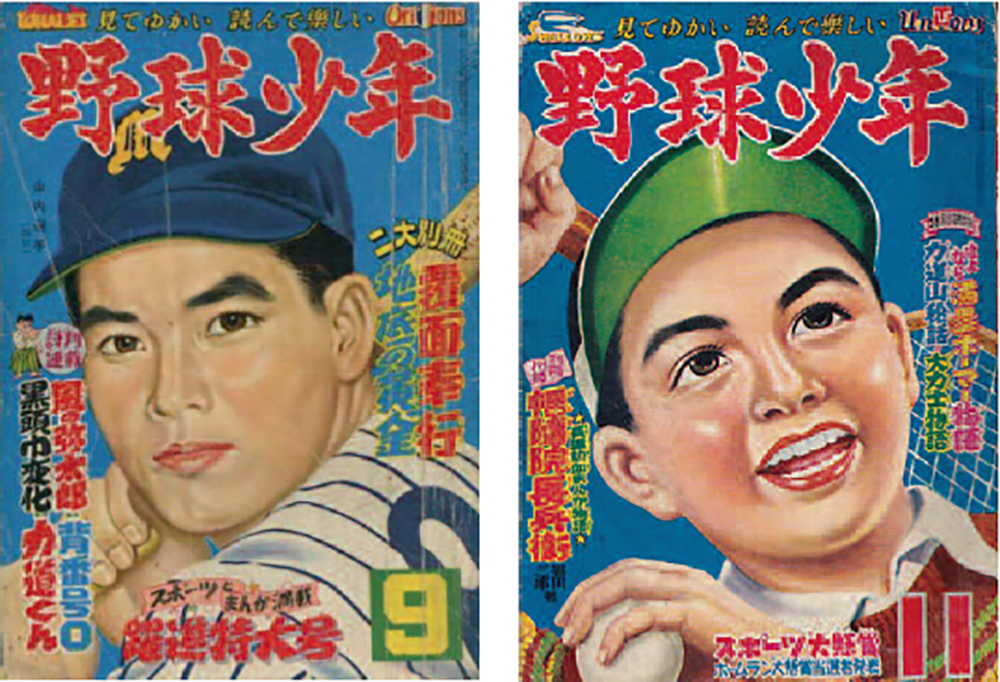

Launched in 1947 by KATO Ken’ichi, Yakyu Shonen was the first magazine for young people dedicated to baseball.

Baseball plays a large role in manga but you have to go back in time to find out why.

The history of sports manga officially started in the mid-60s after the Tokyo Olympic Games, but 20 years earlier there was a man who laid the foundation for the huge success of such titles as Kyojin no Hoshi, and that was magazine editor KATO Ken’ichi (1896-1975). When people talk about the “Golden Age” of Japanese comics, such artists as TEZUKA Osamu, FUJIKO Fujio and ISHINOmORI Shotaro are bound to be mentioned. However, not many fans know KATO, a perceptive and forwardlooking man who first nurtured the skills of above-mentioned artists. During the second half of the 1940s and early ‘50s the late magazine editor was responsible for assembling a formidable staple of young talent, which went on to create some of the most popular titles in the history of Japanese comics.

KATO’s early interest in children’s magazines began when he was still working as an elementary school teacher in his hometown in Aomori Prefecture. After realising their potential as both an entertainment and educational tool, he first created a school magazine with a mimeograph. Then he moved to Tokyo in the early 1920s, found a job at Kodansha (one of the capital’s major publishers) and became the editor-in-chief of the children’s magazine Shonen Club when it was having problems finding a steady readership. KATO immediately made several changes, like including TAGAWA Suiho’s Norakuro and other hit manga stories, and propelled the magazine’s circulation from fewer than 30,000 to 600,000 copies.

In the late 1940s, KATO would apply his magic editorial touch to an even more successful children’s magazine, Manga Shonen, but we are here to talk about a third project that, though short-lived, opened the way to the later advent of sports manga: Yakyu Shonen [Baseball Boy] magazine. At the end of the Pacific War, KATO resumed work at Kodansha, but became the victim of the purge campaign ordered by the Japan-based General Headquarters of the Allied Forces (GHQ). After his name ended up on the list of banned people, KATO left Kodansha and started working on a new publishing enterprise. He enlisted the help of his professional acquaintances and even his family to establish a small publishing house in his home. His wife was listed as the official owner in order to let KATO’s activity fly under the GHQ’s radar. Ironically enough, he chose baseball as the new magazine’s theme. KATO knew absolutely nothing about the American sport, but he thought that a baseball magazine was bound to be successful. After all, GHQ was promoting baseball as a wholesome and healthy physical activity. As major General William marquat said, “the Japanese love the emperor and baseball, and we will use both of them to keep them in check.” Indeed, in 1946, while the country lay in ruins and millions of people had neither food nor a place to live, both professional baseball and the Tokyo Big6 intercollegiate league were allowed to restart.

Marquat was right about the Japanese love for baseball, as sporting entertainment was one of the very few things people could be cheerful about. The two biggest stars of the day were yomiuri Giants first base KAWAKAMI Tetsuharu (“the God of Batting”) and Tokyo Flyers outfielder OHSHITA Hiroshi. KAWAKAMI used a red bat, while OHSHITA’s was painted blue, and both made good use of their bats by smashing records and winning multiple batting titles. Japanese kids worshipped them. Their love for the “red-bat” and “blue-bat” stars was such that when they went to the public baths (a daily routine at the time) they all wanted to use lockers number 16 and 3 – KAWAKAmI’s and OHSHITA’s numbers respectively.

Nowadays, television and even the internet are so pervasive that we take video-watching for granted, but in the late 1940s, when most houses didn’t even have a TV set, just reading a magazine article or a poem (e.g. SATOHachiro’s “I Saw It with My Own Eyes” about KAWAKAmI’s exploits) had the power to inflame people’s imagination. Yakyu Shonen tapped into the country’s baseball fever. Apparently KATO had never seen a baseball game in his life, but he believed that one should always try new things. So he wasted no time in getting a sports education. Korakuen Stadium (home to the yomiuri Giants) was located near his housecum- office in Hongo, central Tokyo, and he started taking his kids to the ball games. There he would pester them with questions in order to learn baseball’s intricate rules.

KATO may have been a newcomer to sport, but he was a first-class editor all the same, and knew how to attract the best talent to his magazine. One of the biggest media personalities at the time was SHImURA Seijun, a radio commentator who broadcast baseball games live on NHK, Japan’s public radio. KATO convinced SHImURA to work for Yakyu Shonen, and his play-by-play commentaries, turned into articles, became one of the magazine’s main selling points. Giants manager mIHARA Osamu became an editorial adviser and would often visit KATO’s home.

Yakyu Shonen quickly reached a circulation of 400,000 copies, a staggering number considering the circumstances and limited financial means with which it was produced. Once again, KATO had achieved the goal he had strived for teaching in Aomori and self-producing mimeographed magazines: making children happy by publishing good quality papers. He had gambled his life and the life of his family (his ever-understanding wife and seven children) and produced another smash hit. However, despite the magazine’s huge success, KATO himself was less than satisfied. entertaining the masses was good, but for him, a magazine was a powerful means to educate people, and the ethically- minded KATO could not be content just publishing baseball stories and photographs of star athletes. In this respect, his vision and editorial philosophy had not changed since the time he had worked at Kodansha. For him, Shonen Club remained the gold standard against which to compare all the other magazines, and KATO quickly came to the conclusion that he wanted to create a similar title.

At the time, he was already 51, but his family’s precarious financial situation was the least of his concerns. As he wrote in his notes, “In today’s Japan, the war-defeated adults are useless. We cannot trust them to rebuild our country. Instead, our hopes lie with our children. Only by educating and inspiring them can Japan hope to rejoin the world’s cultural elite. In order to achieve this, we have to instil once again in our children the idea of beauty: the beauty of art and the beauty of science. Only by loving beauty in its multiple forms can one develop a strong and right mind.” So KATO put an end to Yakyu Shonen and embarked on yet another adventure. The new magazine, Manga Shonen, first appeared in December 1947 – less than one year after the launch of Yakyu Shonen – and continued publication until 1955 for a grand total of 101 issues in eight years.

The magazine’s name, Manga Shonen, had a double meaning: on the one hand, teenagers were its target readership; on the other hand, aspiring artists from all over the country were invited to send in their work, and the best stories were published in the magazine. Thus KATO became a sort of father to many young manga artists, and the legend of Tokiwa-so (the apartment building where many of them lived) was born.

But, as they say, that’s another story…

G. S.