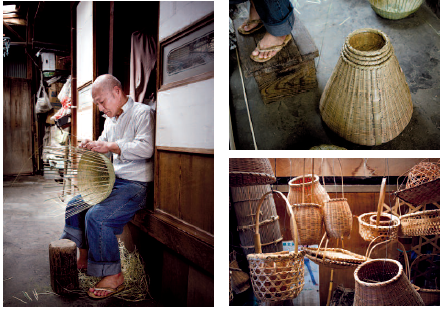

A late-comer to bamboo weaving, he learned everything from his father.

A late-comer to bamboo weaving, he learned everything from his father.

Bamboo craftwork has a long history in Japan; excavations have revealed finely woven and lacquered baskets dating back to the late Jômon period (1100-300 B.C.). Most likely imported from China, the techniques used in Japan have evolved over time with the development of the middle classes during the 17th century. Wishing to access high quality products in order to imitate the aristocracy, they tried to purchase the same objects. The great demand favoured the emergence of the basket maker (kagoshi), who progressively developed a new body of technical knowledge inspired by Chinese techniques. The new techniques produced beautiful objects that supplanted the market for Chinese inspired products. In his remarkable book “The Spirit of Bamboo” (Philippe Picquier editions, 2004), Dominique Buisson explains it thus; “the basket maker’s craft is close to calligraphy in the same way that the empty and full spaces are balanced as the breath of what is not painted in the ideogram is in harmony with the black mark left by the gesture.” Miyata Hiroshi does not contradict this. He is a specialist bamboo craftsman, and has spent his life manipulating and weaving this plant. “I have been making baskets (zaru) and other flower baskets (hanakago) for 45 years now,” he says. He learnt basket making from his father somewhat late in life. “I was 30 years old,” he admits. “I had been a cook in a sushi restaurant, before developing an interest in weaving and its basic techniques”. Only the outer part of the bamboo is used to make most of the objects. To obtain it, the craftsman needs to split bamboo that has been left to dry for a whole year since it was harvested. The splitting is done vertically (tatewari) and by successively reducing the width of the strips horizontally (yokowari). He repeats these movements day after day. Despite all his years of experience, Miyata Hiroshi is still humble about his work. Some steps, such as splitting the bamboo by using the mouth (kuchihagi) are very subtle. It involves dividing the strips in two without being able to see them, and by holding their extremities between the teeth. One must take care not to split them to the ends in order to preserve their strength. Many years are needed to master all these movements and the weaving itself requires knowledge of the many methods that allow one to make the best use of thedifferent strips. Each of them is different, which means that every basket is unique. The objects that Miyata Hiroshi makes have acquired a great reputation. “I receive orders from all over the country,” he adds. But when he stops, there will be no one to follow him. He did not have any children, so was unable to hand down the methods like his father did. He might regret this, but does not say so openly. Focused on the weaving for a new order, his eyes are fixed upon his work. With steady movements, he assembles the strips one after the other. Time seems to stand still. Miyata Hiroshi is at work.

O. N.