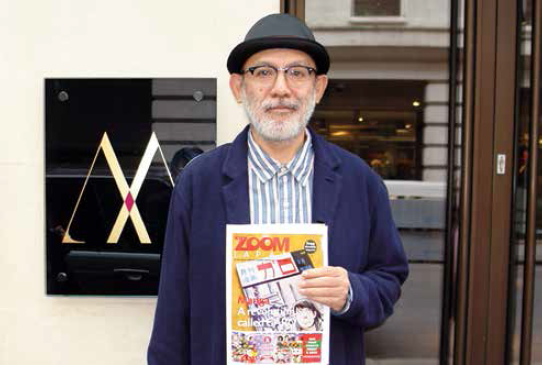

Born in 1958, HARA Kenya is art director of Muji since 2001 and designed the opening and closing ceremony programs ofthe Nagano Winter Olympic Games 1998. He has published “Designing Design”, in which he elaborates on the importance of “emptiness” in both the visual and philosophical traditions of Japan, and its application to design. In 2008, Hara partnered with fashion label Kenzo for the launch of its men’s fragrance Kenzo Power. He is considered a leading design personality in Japan and in 2000 had his own exhibition “Re-Design: The Daily Products of the 21st Century”.

Born in 1958, HARA Kenya is art director of Muji since 2001 and designed the opening and closing ceremony programs ofthe Nagano Winter Olympic Games 1998. He has published “Designing Design”, in which he elaborates on the importance of “emptiness” in both the visual and philosophical traditions of Japan, and its application to design. In 2008, Hara partnered with fashion label Kenzo for the launch of its men’s fragrance Kenzo Power. He is considered a leading design personality in Japan and in 2000 had his own exhibition “Re-Design: The Daily Products of the 21st Century”.

How do you evaluate the meaning of “made in Japan” today?

HARA Kenya : I think that the “made in Japan” label, that goes back to after the Second World World, has no more reason to be nowadays. Industrially speaking, the production and conception of exportable products isn’t adapted anymore because all the other Asian countries are doing the same thing. Basically, I think we’re experiencing the end of the after war “made in Japan”. That is why it is necessary to try and define a new concept of what “made in Japan” is. We’re at a very important time between two eras.

How should that take form?

H. K. : Until now, at the industrial level, Japan privileged mass production that was characterized by high quality. Nevertheless, the rest of the world is now producing according to these norms, and Japan doesn’t have the means to compete with the same products at lower costs. Thus the new “made in Japan” needs to develop according to other criteria, such as aesthetics. Japanese culture is ancient. And it depends on a homogenous and millenary history. It’s an important asset from which an original concept, turned towards the future, could rise. We need to forget about televisions, fridges, and turn towards living, the sense of welcome, tourism, or even medical assistance that are important fields for the archipelago’s

future.

And what is your role in defining the concept?

H. K. : As a designer and an artist, I offer clues for the future and try to imagine what could happen.

Could you develop your concept?

H. K. : Culture is related to quite a limited territory. It can be linked to a local vision of things. But we can also ask ourselves if Japanese culture can bring a contribution to the rest of the world. During peak growth years, the Japanese never tried to project their culture further than their borders. All they were thinking about was money and circulation. Culture, in its aesthetic dimension, was completely neglected. But that isn’t the case anymore. We are now in an era of maturing of the Japanese culture. Take housing as an example. In the past, the house was considered a belonging only, of commercial value like others. It wasn’t thought of as a space in an environment. Japan was nothing but a wide factory. The whole territory was covered with factories because everything was seen from an economic angle. But all of that has changed. We have attained a new maturity. We are now capable of considering nature under a new light, and seize all of its beauty. If we add our quality requirement to that, I think that it will now be possible to promote local tourism. By putting that to use and remembering that Westerners were able to export their culture of hotels in the past, I think that the Japanese can do the same thing. In Japan, there is that sense of welcome and hospitality that we can make use of to imagine a new exportable made in Japan product. On the other hand, it is still maybe too early to start launching our concept of housing, because there are cultural obstacles to overcome. Nevertheless, there are many possibilities relating to aesthetics. Our first objective has to be Asia. In the past, we focused only on the United States and Europe marketwise, with electric ware and cars. Now, we need to look towards the Asian continent where local culture, without being Japanese, has a base to which we can add new elements from our own culture, yet that are adapted to the local needs. We cannot consider exporting Japanese housing to China or Indonesia yet, because it wouldn’t be very well perceived. Thus, we need to move forward progressively and melt into the local culture. I would really like to contribute to that reflection.

Recently, a Japanese company opened a traditional Japanese hostel in Taïwan where everything is traditionally Japanese, the service included. Do you consider that as being a good example of what should be done?

H. K. : That’s not really my idea. What has been done in Taïwan is what I consider a kind of exoticism, meaning that it doesn’t really correspond to any local need. A Japanese model was exported without taking in account the local ways, that’s all. In traditional Japanese hostels, service is sometimes quite rigid. For example, I’m thinking of diner that is served quite early. That doesn’t necessarily correspond to what customers are expecting in other countries. On the other hand, service fundamentals such as politeness, simplicity, care and delicacy should be highlighted and adapted. What I mean is that in its post-growth version, “made in Japan” needs to be linked to a different way of thinking. It relates to the idea that culture, in it’s general meaning, is an essential ingredient for developing on other markets, as long as the local needs are considered. The Japanese could create very original hotels in Asia by offering service fundamentals, but also by allowing the customers to take advantage of them at their own rythm. It’s not any more complicated than that, but there are constraints that should be respected.

Interview by O.N.

Photo: Odaira Namihei