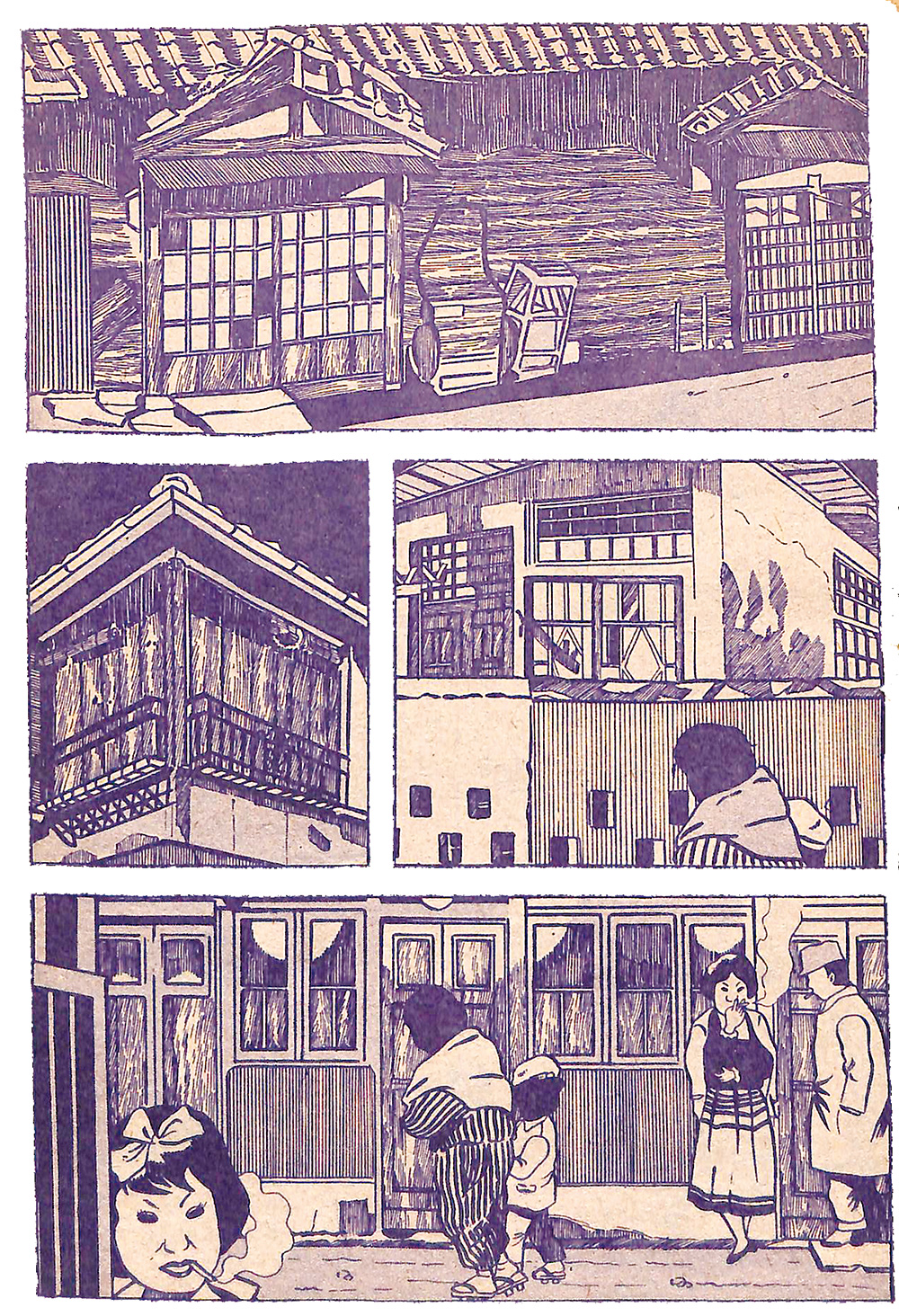

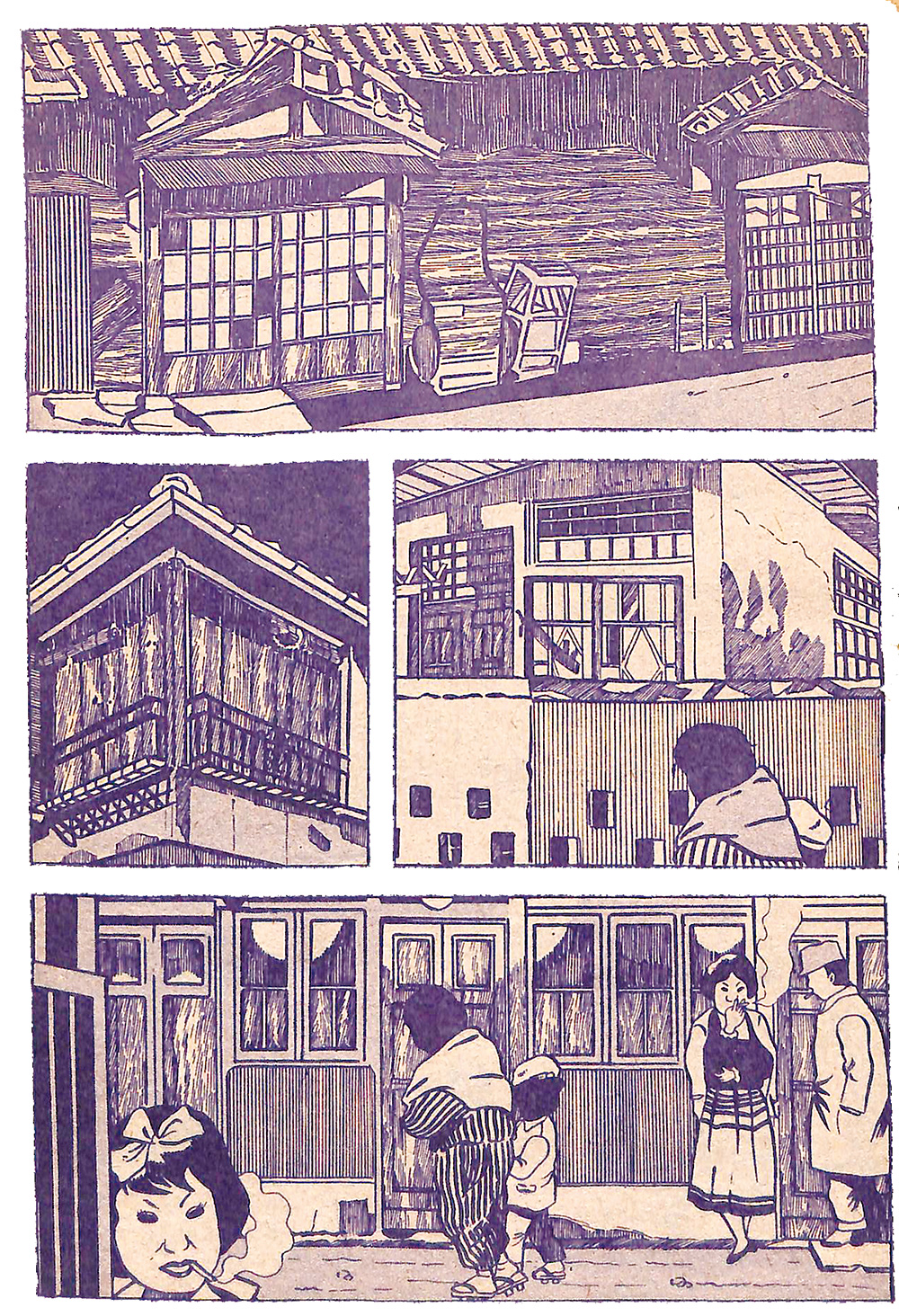

Tadao was very inspired by the red-light district of Tateishi. An extract from Garo no. 58, April 1969.

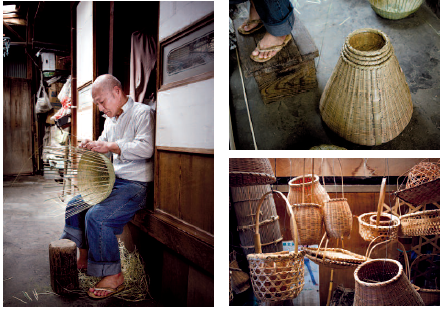

In his work, the mangaka has often depicted working-class districts like Tateishi, where he has lived for a long time.

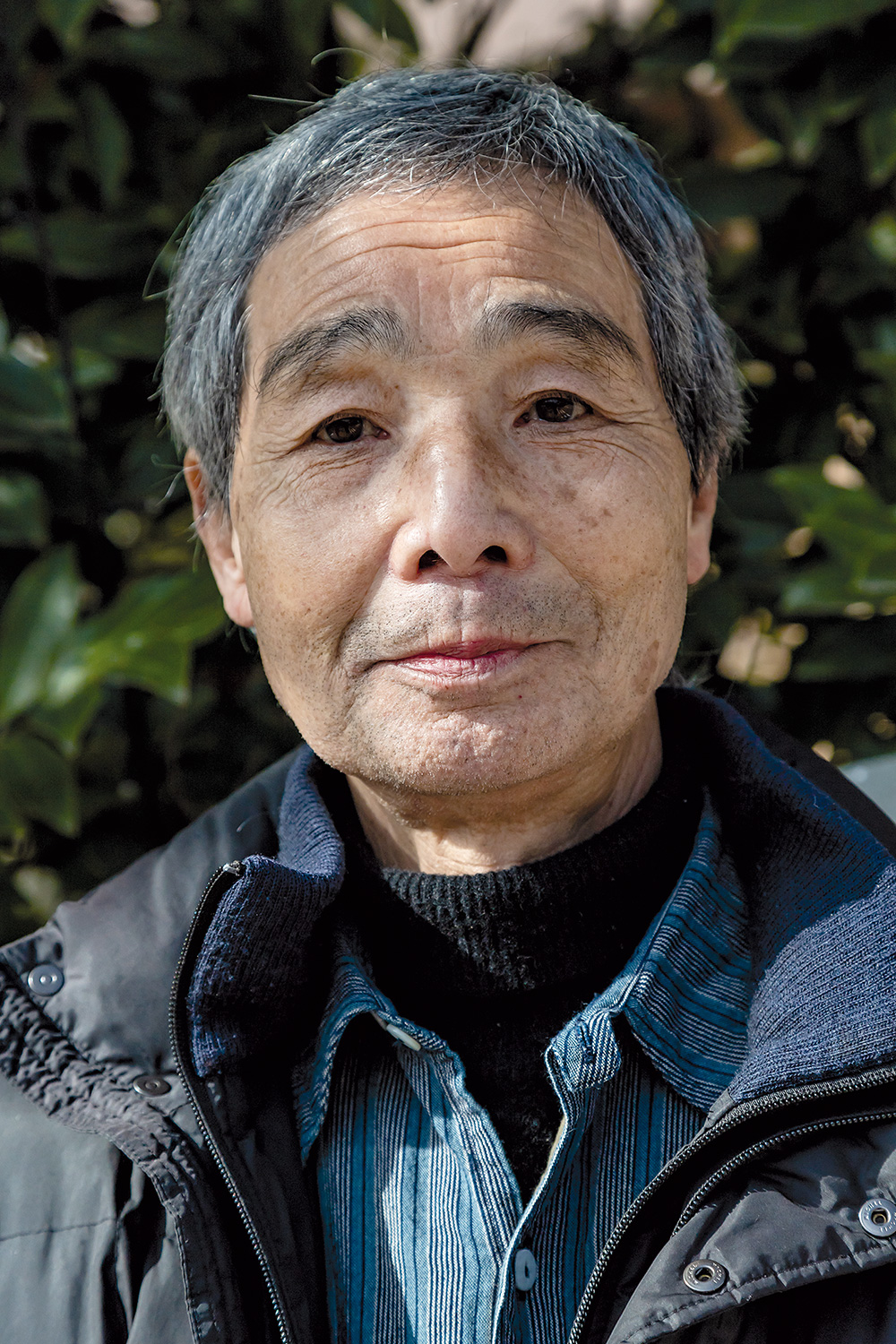

Tsuge Tadao is the stuff of legend. until quite recently the veteran comic artist – still active at 78 – was almost unknown outside Japan, yet he was one of the pioneers of alternative manga and a key contributor to avant-garde magazine Garo between the late 1960s and early 1970s. In contrast to his older brother and fellow mangaka Yoshiharu, Tadao has extensively portrayed, in unsentimental tones, the gritty life of common people and their daily struggles in postwar Japan. Many of his stories are based on his first 20 years of life spent in Katsushika-ku, first in Tateishi and then in Aoto. He shared some of these memories when I met him some time ago.

Tsuge was born in a small fishing village in Chiba Prefecture, but his father died when he was only a year old. After his family moved to Katsushika, his mother remarried and the child’s life took a turn for the worse as he suffered continual abuse from his stepfather and maternal grandfather who had joined the family from Chiba. As Yoshiharu and his other older brother started working to help the family make ends meet, the young Tadao was left to fend for himself during the harsh postwar years both in and out of home.

He shows me two scars on his arms, a memento of his troubled childhood. One is the result of abuse by his grandfather. The other is from treatment his grandfather gave him after he suffered a serious injury. “Any excuse was good enough to escape my home,” Tsuge says. “even when I grew up and was less afraid of the beatings, I couldn’t stand being at home. sooner or later, I would go out into the street, looking for friends or to catch a glimpse of the prostitutes.” Tateishi at that time was a strange mixture: a bustling working-class area with a plywood market and a red-light district. The whole district was full of small-time gangsters, prostitutes, Korean immigrants, and other undesirables. “It was rundown and stank of sewage,” Tsuge says. “The houses were separated by a maze of narrow streets, and there were gutters everywhere, sometimes nothing more than a roughly dug ditch. Like many other shitamachi districts in eastern Tokyo, it was populated by two kinds of slimy creatures: the sewers were colonised by millions of botta (Tubifex worms) while the streets were full of crooks. Curiously enough, for the most part the crooks were as peaceful as the worms.

They would usually loiter on street corners or around the black market, but they rarely fought one another. They just squatted or stood around with nothing to do, looking lost. I guess the neighbourhood wasn’t large enough to attract the big boys – the yakuza.”

Though Tsuge himself was never a gangster, he was attracted to Tateishi’s underworld and was fascinated by some of its more colourful characters. One of Tsuge’s latest’s english translations, Tale of the Beast (Black Hook Press), is the story of OGURA Kiyohiko, a serial killer whose past somewhat resembles Tsuge’s childhood years. “Tale of the Beast was inspired by some of the people I saw in the street,” Tsuge says. “One day I saw a woman in the street, and then a gangster. somehow, they left an impression on me. For a kid like me who had nowhere to go, they embodied the idea of freedom. I started imagining their life and ended up with Tale of the Beast.”

After the war there were no jobs and precious little food, and the Tsuge brothers were always angry. “Katsushika was famous for its high concentration of celluloid (plastic) factories,” Tsuge says. “My brothers and I stole some toys we found stored in the building where we lived, and began to sell them at local festivals together with ice lollies, once or twice a month. We spent our earnings on sweets and manga, particularly TEZUKA Osamu’s stories.”

Prostitutes were among Tsuge’s customers. “I remember one particular summer night,” he says. “I was selling ice lollies with my two brothers on the street that went through the red-light district. We had an ice box and next to it a container with hand-made lottery tickets folded into triangles. On a cloth spread on the ground, we arranged the plastic ducks we had stolen to give away as prizes. We’d inherited this business from our stepfather’s friend after my stepfather fell ill and became too weak to work.

“On this particular night, two or three girls from a nearby brothel came by to buy ice lollies. One of them drew a winning ticket. she was so overcome with joy that she let out a scream. I was mesmerized by their heavy makeup – their white faces caked with powder and bright red lips. They looked so beautiful to me. Well, any girl had that kind of effect on me at the time. Ridiculous as it may sound now, as a kid, I honestly thought that once I became an adult I would protect those girls.”

TSUGE Tadao lived in Tateishi for many years. He remembers it vividly.

Among the thugs that lingered about Tateishi, one particular man who ended up capturing Tsuge’s imagination was a guy nicknamed KeIseI sabu who stars in several of his comic stories. “Actually, the KeIseI sabu I portrayed was more the fruit of my fervent imagination working at top speed,” he says. “Though I lived in Tateishi for more than ten years, I saw him only a couple of times. I didn’t even know his real name. The second time, I was around 13 and saw a stinking drunk guy dragging two other ruffians down the street. A shop owner said it was sabu, that’s the only way I knew it was actually him. Well, I guess it was for the better that I knew so little about him because he was most probably a good-for-nothing; one of those types who keep making one bad decision after another. But because I knew nothing, my imagination was free to come up with any kind of story about him. And anyway, I’ve never been interested in heroes.”

Though Tateishi was a pretty depressing place, when Tsuge was a child there were four or five cinemas, and between the age of seven and 12 he got into the habit of seeing two or three films a week. He not only loved the films, but those dark places were also a refuge from the domestic violence he was escaping from.

“My first film-related memory is probably watching Muhomatsu no issho (Rickshaw Man) in 1947 or 48, when I was around six. someone must have taken me to see it, but I forget who it was. A few years later, I saw Kanashiki kuchibue starring the then 12-year-old MIsORA Hibari. But to be completely honest, I was mad about foreign films, starting with all Johnny Weissmuller’s Tarzan films. They were so cool! “The problem was how to get into those cinemas without paying because I was always penniless. However, I knew a few tricks. For example, pre-school age kids got in for free when accompanied by an adult. even when attending elementary school, I was so small that I could pass for a younger kid, so I would walk into the cinema right behind a stranger as if I were his son. unfortunately, I eventually grew too tall to use that particular trick, so I changed tactic. I began to rush into the cinema in the middle of a show screaming that there was an emergency at home and I had to find my mum. The cashier was usually kind enough to let me in.”

After finishing junior high school, Tsuge found a job at the local blood bank – a place where people in need of money sold their own blood. For Tsuge, this place became another source of story ideas. “I had a chance to meet many people like sabu,” he says. ”Though I was only 15, I felt I understood their motives. It was as if I could see through them. As a kid who had grown up being beaten at home on a daily basis, I had become good at reading people’s faces. each one of them had a different story to tell, a different past, but they all shared the same war memories. Just by listening to them talk, I was able to imagine their life. My stories, in this respect, were just an accumulation of all these bits and pieces, filtered through my imagination. Telling those stories was a lot of fun.”

Tsuge eventually left Katsushika when he got married at 24. “I moved to my wife’s city, where we lived with her family and I joined their business, working in a hardware store and selling gas. It was a much better life, but still, I have to thank Tateishi for inspiring me.”

G. S.