For ages, this quiet port city situated by the Inland Sea has attracted appreciators of tranquility and good food.

For ages, this quiet port city situated by the Inland Sea has attracted appreciators of tranquility and good food.

The town of Onomichi, on the Seto Inland Sea Coast, is a living monument to literature. Its great beauty has been inspiring writers and artists for centuries. It was even mentioned in the Manyoshu, the oldest known anthology of Japanese poetry. Legendary haiku master Matsuo Basho spent time there in 1689. More recently, movie director Yasujiro Ozu chose Onomichi as the archetypical Japanese hometown for his classic 1953 movie, Tokyo Monogatari (Tokyo Story). German director Wim Wenders loved Ozu’s film so much, he made his own pilgrimage to the town fifty years later and published a book about it; Journey To Onomichi. However, film and literature aside, Japanese people also appreciate Onomichi for something that, to Western visitors at least, may have less obvious cultural appeal: ramen. People come from all over Hiroshima Prefecture and beyond for a hearty bowl of Onomichi’s finest noodles. Long queues form outside the town’s more popular ramen restaurants, which even place kerosene stoves outside in winter to keep waiting customers warm.

The easiest way to explore Onomichi is to take the ropeway (built in 1957 and just a short walk from the station) up to Senkoji Park, 500 feet above the town. The short ascent is breathtaking as you glide above the canopy of pine trees that clad the hillside. At the top, you are rewarded with stunning views of the entire town and the many misty islands of the Seto Inland Sea. The view is even grander from the Park’s flying saucer-like observatory, the town’s highest point.

On a clear day you can see across to Shikoku, Japan’s fourth largest island. Inside the observatory, a restaurant offers your first chance to sample the local ramen.

To get back into town, take a stroll down the steep, winding trail known as the Path of Literature. Dotted among the fragrant pine trees, echoing with the sound of cicadas, you’ll find twenty-five boulders, each inscribed with a quotation from some of the famous literary figures associated with the town. These range from ancient folk songs to 20th century writers like the feminist Fumiko Hayashi. Even if you can’t read Japanese, you can’t help but feel uplifted by this outdoor art gallery. It’s also fun to wander off the trail and get lost down twisty alleys, where Onomichi’s famous cats snooze in the shade and quaint tea-rooms cuddle into the folds of the hillside.

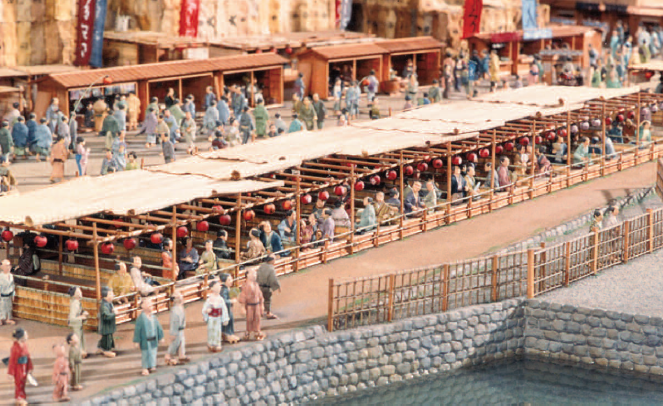

Halfway down the Path of Literature, prepare to be amazed by the vermillion-lacquered glory of the Senkoji Temple, with its famous Kyo-onro bell-tower. Established in 806, it’s one of Onomichi’s most iconic symbols. Many students come to Senkoji to buy omamori (amulets), believed to bring them luck in their exams. The sound of the Kyo-onro bell has even been designated as one of “Japan’s 100 soundscapes that need to be preserved”. Near the bottom of the hill, look out for Tenneiji Temple (built in 1367), famous for its three-storied pagoda. In fact, you could easily spend a day, or longer, just visiting the temples. Onomichi is home to more historic temples per square mile than any Japanese town outside Kyoto. Most were built through the donations of rich medieval merchants when Onomichi’s port, which dates back to 1168, was booming with trade. The Historic Temple Walk, which takes you round twentyfive of the town’s most interesting temples, is a good country mile, up and down the Old Town’s labyrinth of steep streets and alleys. Some temples, like Saikokuji – the one with the giant rope sandals hanging outside, date back to the 8th century. It’s a walk not to be hurried, but savoured.

Back down in the town centre again, it’s time to explore the seafront area and Hondori, the covered shopping arcade. Most of the ramen shops are in this area. Some, like Shuka-en, regularly have queues outside of up to 100 people. It’s also worth checking out the little dried fish shops. Look out for the fossil-like objects, which are actually senbe, or rice crackers, with whole dried fish or octopus baked inside them.

In a typical ramen bar, jars of help-yourself condiments stand on the counter, from pickled ginger to whole, peeled garlic cloves. Service is swift, as the waiter places before you a steaming bowl of noodles topped with heaps of chopped spring onions and other vegetables, plus a generous slice of pork. The stock is thick and creamy, making for a perfect pick-me-up after a morning’s sightseeing. If you’re really hungry, do like the locals and ask for a side order of onigiri (rice balls with salmon, seaweed or fish roe filling) and gyoza (meat dumplings). No one seems to agree about what makes Onomichi ramen so special. “It’s the pork bones in the broth” say some. “It’s the flat noodles,” say others. “No, it’s because they use soy sauce instead of miso in the stock,” insist a few. But one thing is certain: a trip to Onomichi will change your mind about ramen forever.

Steve John Powell

Photo: Steve John Powell