This French jazzman found not only inspiration in the archipelago, but also the desire to share his musical knowledge.

This French jazzman found not only inspiration in the archipelago, but also the desire to share his musical knowledge.

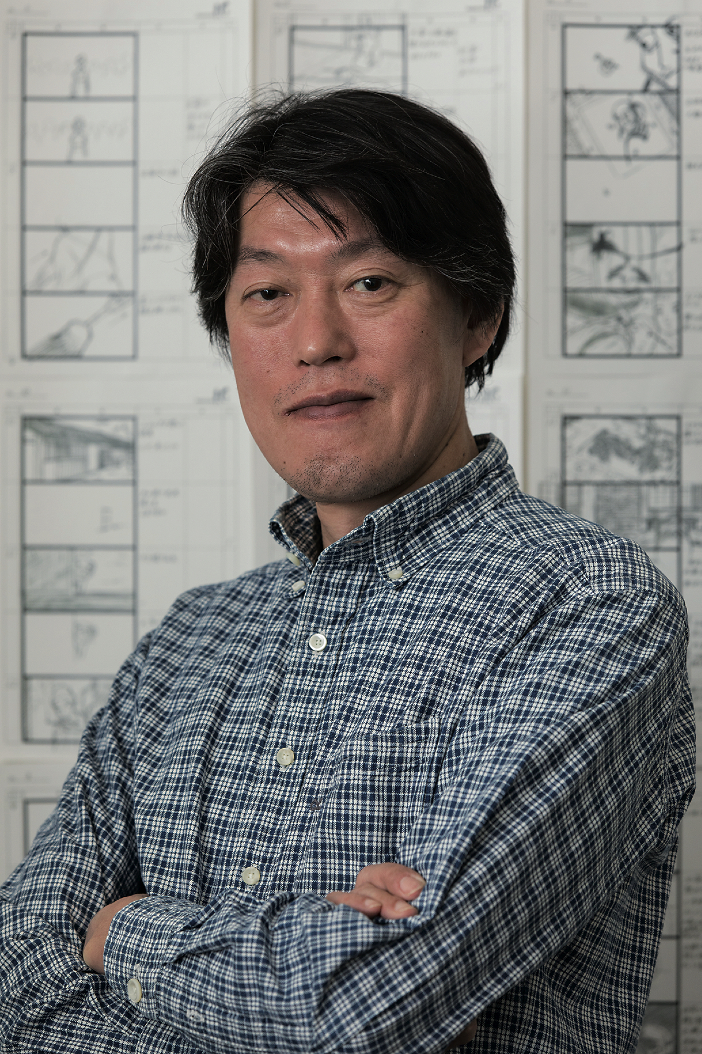

For over 28 years, Dominique Fillon, pianist and colourful jazz composer, has enchanted us with his music inspired by African and Brazilian rhythms. Yet it’s in Japan, a world away from those hot climes, that he chose to launch his new musical project. Born on the 25th of February 1968 in Le Mans, Dominique fell head over heels for this country in 2009. He returns regularly to conduct different professional projects. Now he shares his vision with Zoom Japan and gives us the key to understanding why the Japanese are particularly drawn to jazz.

Tell us how you discovered Japan.

Dominique Fillon: I came with my wife, Akemi at the end of March 2009, at the time of the sakura blossom, to visit her family in Omiya. It was so cold in their traditional Japanese house (except for the kitchen, which was too hot) that we left for Tokyo. And that’s where I realized that jazz was everywhere: in the shops, offices… Miles Davies on trumpet. No one else listens to jazz as much as the Japanese. From the very beginning, I was touched by the people, how much they smiled. There is a real culture of hospitality here. No matter where you go, people are happy to welcome you, something that you don’t experience anywhere else in the world – especially not in France (laughs).

In 2011 after the Tohoku earthquake, you and your family became involved in helping victims. What did you do?

D. F.: The same morning the news of the tragedy reached France, Akemi – a professional violinist – wrote a piece of music in honour of the victims, called Sakura 2011. “The notes represent all the lives that have flown away,” she told me. It was very moving. Then, a month later, when I was leaving the stage after a performance, a businessman came up to me and asked if I would like to organize a fundraising concert in Tokyo. He told me to choose a cause, and I wanted to support musicians, as we were musicians ourselves. We decided to buy new instruments for a school from this region, which had lost everything. On the night of the concert, many local people came, all very dignified. Nearly all the women were wearing their furisode (ceremonial kimono). One of the young girls from Fukushima School came up on stage to receive a symbolic violin. We raised more than £30,000 for the instruments. What an incredible moment!

Jazz is much appreciated in Japan. How would you explain the Japanese affinity for this kind of music, and particularly for your own music?

D. F.: I don’t play the type of jazz they’re used to listening to. When the Japanese talk about jazz, they are thinking of Miles Davis and other famous names. Often they enjoy this music without really understanding it. They appreciate its aesthetics and the atmosphere it creates without realizing everything it represents or understanding its history. They don’t necessarily know that this type of music is improvised, for example. They appreciate my music, but not necessarily because they like jazz. It goes beyond that. My music pleases them because of the feelings it produces. They enjoy the emotions I express through the notes and the way I play. This means I can play anything I want! (laughs)

What is it about Japan that inspires your music?

D. F.: Since my childhood, I have repeated all the sounds that I hear. I am very sensitive to the melody of the Japanese language. There are always new sounds to be heard, and because my brain is wired in a particular way, like a hard drive, it makes connections… the sounds of the language inspires me by reminding me of the sound of Bambara or Swahili. I was particularly moved by the Meiji Shinto Shrine in Tokyo, close to Omotesando. So I named one of my pieces after it, keeping in mind this place and the magnificent park it is set in. Above all was the elegance of the sound – Omotesando. It’s a word that bounces, it is very exotic and almost sounds African. The creative process was very different for Abounayo – “Watch out!” in Japanese – a track from my last album, Born in 68 (Crystal Records), that came out in June 2014. I started to compose the song using the sound of these soft, wet words and this jazz-rock music just came to me as I repeated it several times into the microphone.

Your music is heavily influenced by Brazilian music, sensual and warm, and you, yourself appear to be very open and communicative… So what was it about Japan that seduced you, a country where there are a lot of restrictions and where discretion is ingrained?

D. F.: I am even more of an extrovert in Japan, where I have no boundaries. I enjoy the way the Japanese regard me, it encourages me. When you get the opportunity to work together, they are the first to want to share their feelings. Even if they are discrete and never do so straight away. The complete opposite of Americans! However, once the door is open, they are very outgoing.

How do Japanese artists tackle improvisation, how do they go about it? Do you have any stories to tell us?

D. F.: In September 2015 I did a series of concerts at the French Institute of Tokyo. A young Japanese saxophonist, Sarah Maeda, was invited to join our trio. If Sarah hadn’t known how to improvise, I wouldn’t have invited her. We did a jazz concert full of improvisation! Jazz is instantaneous composition within a given framework. First the players lay down a musical theme, then extemporize around it. It makes for a complex performance, composing on the spot in front of an audience. Sarah did very well.

Soon you are organizing a performance in France bringing together jazz and rakugo. How do you expect to combine these two art forms?

D. F.: Have you heard about the themed evenings called Wine and Jazz organized in the castles of Bordeaux? It’s the same concept. To listen to jazz one needs a certain sophistication. It’s an art form that requires a degree of attention, and you appreciate it more if you’re very familiar with it. I believe it’s the same for rakugo. At first, this comedy storytelling dating back to the Edo era is, frankly, rather surprising… then you discern something delicate and elegant behind those apparently simple comic tales. I wanted to organize an event that brings together the qualities they both share. It’s a first!

What else are you currently working on in Europe and Japan?

D. F.: I continue to perform concerts in France or elsewhere, either solo or with my trio. I go where I’m invited. I’ll be performing in Kyoto and Tokyo in February. But coaching artists in Japan is the project closest to my heart at the moment. As a professional musician for the past 28 years, I’ve played with and directed artists in many different contexts all over the world. I’ve come to a point in my life where I want to give something back, more than I want to perform. Usually, in Japan, you’re able to bring something new to the table. I offer Japanese musicians “know-how” that has nothing to do with a specific kind of music or style. To be a professional musician means knowing how to become very proficient at bringing order to a multitude of details. I know how to do that and enjoy passing that skill on. I help artists make progress in what they want to do. The first people I coached in Tokyo studios have already thanked me for the progress they’ve made. With my help, their instruments have finally become an extension of their minds!

Interview by RAPHAÈLE LESORT

Photo by DR