At the age of 78, Sakamoto Masahide is still passionate about his profession as a confectioner.

The first thing one notices about Sakamoto Masahide are his hands. His thick stubby fingers are the result of 60 years of stirring red beans and sugar, pounding and moulding glutinous rice, and using a vast array of tools to create his famous wagashi (Japanese-style confectionary). A visit to his shop, Eitaro, is a must for food lovers with a sweet tooth. Even, today, at 78, Sakamoto-san never tires of making and talking about sweets.

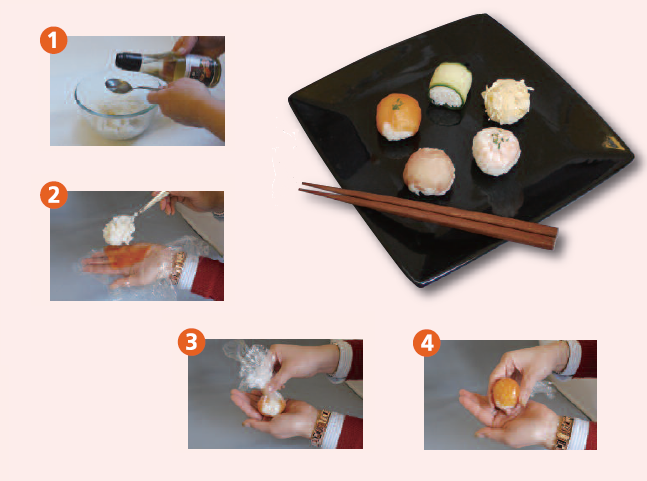

“There are so many wagashi that I could spend hours talking about them,” he says. “On one hand, there are asanama and jonamagashi, which are mochi-based fresh sweets that are supposed to be eaten on the same day. Then you have yakigashi (baked sweets) like dorayaki (Doraemon’s favourite food) that consists of two small pancake-like patties made from ‘castella’ sponge cake wrapped around a filling of anko. Many wagashi take on particular shapes and design depending on the season.”

Though wagashi come in many shapes, their basic ingredients are almost the same, starting with anko, the red-bean paste that comes is several varieties such as tsubuan (whole red beans boiled with sugar), koshian (the most common type, in which the beans are passed through a sieve to remove the skins) or shiroan (white bean paste). “These blue and red sweets you see here, for example, are called oni (demon),” Sakamoto says, “because they are eaten during the Setsubun festival in early February, when we do a little ceremony to drive away the evil spirits. Again, they are made with a mix of anko and a little agar (a jelly-like substance made with red algae) that is passed through a sieve and shaped into cute demon-like figures.”

Wagashi used to be a natural complement to any traditional event.

However, things have changed quite a lot since Sakamoto’s grandfather opened Eitaro’s original shop. “For one thing, there are not as many children as before,” Sakamoto says. “In Japan, as in other industrialised countries, big families are a thing of the past. Now you are seen as a big family if you have even just two kids. Living conditions have also changed. Take the Hina festival. There was a time when people lived in bigger houses and could devote an entire six-tatami room to the hina dolls that are traditionally displayed in early March for the Girls’ Festival (Hina-matsuri). Now, though, the display is much smaller so we don’t get many orders.

“When I was young, a rich lady might have had guests at her home and thrown a lavish tea party. It was an established social practice, which now has almost disappeared. Also, several ikebana and tea ceremony teachers lived in our neighbourhood and taught at home. Whenever they had an event or special guests they would order wagashi to eat with green tea. Now, on the other hand, they do the same things in schools, so we still get orders for seasonal sweets. Last but not least, in the 1940s and ‘50s most people only ate Japanese sweets. Now, though, Western sweets are very popular and there is a seemingly endless choice on offer.”

Eitaro has been doing business in Asagaya for the last 62 years, but originally it was located in central Tokyo. “We were in Hongo, Bunkyo Ward, in what used to be called Harukicho (currently Hongo Sanchome),” Sakamoto says. “Our shop was near the University of Tokyo Hospital. It was a rather small place, about half the size of the current store, with a display case and a café corner where we served things like shiruko (sweet red-bean soup). My father was a hard worker and was always adding to what was on offer. I remember he even made ice cream and sweets, and shaved-ice in summer. We were in a busy street so we had lots of customers. Around New Year, I would help to make mochi (rice cakes), prepare displays and deliver our products around the neighbourhood. It was a small family business so everybody helped out.”

When Sakamoto’s grandfather moved elsewhere, his father took his place at the Harukicho store, and in 1958 moved it to Asagaya, in the western suburbs. “At the time, Asagaya was similar to Nihonbashi and other typical shitamachi (working-class) districts in central Tokyo,” Sakamoto says. “The area south of the railway line, where my shop is, was already a lively place with shops and businesses, many of which were kimono makers, and other related stores selling obi (sashes), tabi (split-toe socks) and geta (wooden clogs).

“Asagaya has always had a rather refined character, quite different from other districts around nearby stations along the Chuo Line such as Nakano or Koenji, which to a certain extent is the same today. However, in the 1960s and ‘70s Nakano Broadway and Sun Plaza went up in Nakano, while department stores and fashionable shopping malls were built in Kichijoji. Asagaya, on the other hand, has become even more laidback. For example, there used to be four or five cinemas around the station, but they are all gone. In this respect, it has been gradually overshadowed by glitzier, trendier areas.”

A couple of years after moving, Sakamoto’s father suffered a cerebral infarction and his son replaced him at the store. “I was only 18 at the time,” he says, “but since I was a child, I had liked to play at being a confectioner while watching my father. My mother always used to help him in the kitchen, so we worked together until I became confident. We came up with new ideas and constantly evolved our approach to sweet-making. Now I’m too old for these things though (laughs).”

Even now, Eitaro is a family affair involving Sakamoto, his wife and son. “Sometimes even my daughter will take a day off from her office job to give us a hand at the counter,” he says. “Only when we are particularly busy, like during Tanabata (Star Festival on July 7), we ask a nearby cake maker to help out as he is not so busy in summer. After all, this is the kind of job that requires manual skills. It’s not something that you can learn in a few days, or you can trust an inexperienced part-timer with. It’s not like making taiyaki (fish-shaped cake) where you only need to learn how to work the machine. Even working at the counter has its challenges because you need to know how to wrap up the sweets nicely. You see, when it comes to wagashi, everything must look beautiful, including the wrapping.”

The design and visual element is the thing that sets wagashi apart from other confectionary. It’s what makes them particularly appealing, and what, according to Sakamoto, makes it such an interesting job. “Of course there is also a downside to it,” he says, “because you cannot repeat what you do over and over again. You always have to create new things and add new flavours to your repertoire because different generations have different preferences. Older customers may be happy with the old favourites, but their children and grandchildren want something new, especially now that everybody is influenced by what they see on TV and the internet.

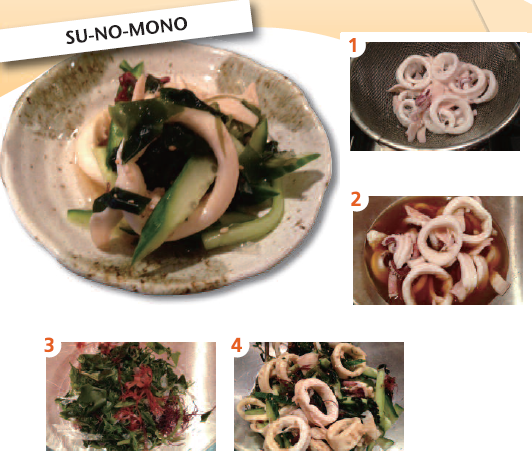

“Cooking and food-production in Japan are traditionally related to the four seasons, with flavours and themes that repeat during the year’s cycle: strawberries and cherries in spring, chestnuts and sweet potatoes in autumn. Then you have matcha (green tea) that is used all year round. But now, everybody follows endless new fads, and the time between one trend and the next seems to get shorter and shorter. Some time ago, somebody invented strawberry daifuku. Until then, nobody had thought about combining anko and strawberries, but it became an overnight sensation. That opened the door to a wide array of anko/fruit combinations – banana, kiwi, the lot – while strawberry daifuku has lost its novelty value and is now taken for granted. It’s an endless battle to think up the next big thing. Now, for example, you have café au lait daifuku – coffee-flavoured anko and cream stuffed in a glutinous rice cake. Even with dorayaki, that I mentioned earlier, anko has been recently replaced with fresh cream. So you spend hours racking your brain to create something new and then maybe nobody buys it (laughs).

“Having said that, traditional wagashi will always have their fans. It’s like a cycle: even those who are attracted to the new, eventually return to the flavours they grew up with.”

Jean Derome