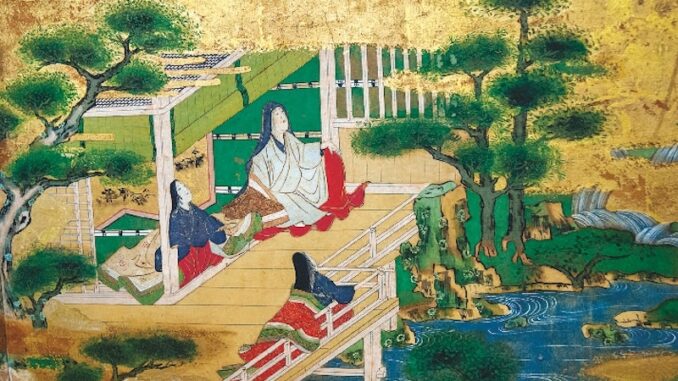

Murasaki Shikibu’s novel gave rise to Genji-e, paintings inserted into the calligraphic text to illustrate the state of mind of the protagonists. / Eric Rechsteiner for Zoom Japan

Written by Murasaki Shikibu in the 11th century, the world’s first novel is still the subject of much debate.

The Tale of Genji is a sprawling novel (Western translations are over 1,000 pages long) with complex themes, which has led to many different readings and interpretations over the years.

Although the story features some 400 characters, the main ones are Genji, also known as the Shining Prince, and a few ladies with whom he is romantically connected, particularly Lady Murasaki.

Genji is the second son of the emperor, but he is removed from the line of imperial succession for political reasons. This, however, does not preclude him from a life of luxury and privilege. The nickname “Shining”, by the way, derives from the fact that he is outrageously handsome, has smooth white skin and excellent fashion sense.

During his life, Genji legally marries twice: first, to Aoi no Ue (Lady Aoi), whom he marries while he is very young, and then to Onna san no Miya (the Third Princess). However, Genji’s most adored lovers are Fujitsubo, the emperor’s wife, and Murasaki no Ue (Lady Murasaki), Fujitsubo’s niece.

Indeed, one of the Tale of Genji’s most talked-about aspects is that Genji has relationships with many women. To be sure, out of the novel’s 54 chapters, the stories concerning those liaisons are focused mostly in the first dozen, but because those are the ones that are remembered and quoted the most, he comes out as an irresistible lady-killer.

Genji’s romantic connections are also viewed in two diametrically different ways by literary critics and cultural commentators. On one hand, his admirers praise him for never breaking up a relationship with a woman and see him as an ideal partner. On the other, though, a growing number of people across the globe are questioning Genji’s behaviour to the point that in Japan, for instance, Genji-girai (detestation of Genji/Genji-bashing) has become quite popular among female readers.

Admittedly, there are moments throughout the story when Genji’s behaviour is appalling. In chapter 20, for instance, his pursuit of Princess Asagao causes him embarrassment, severe grief for her, and mental anguish for Murasaki. Even worse, Genji is accused by some of crimes against women. One such detractor is Setouchi Jakucho, a female novelist who translated the ancient text into modern Japanese. In a 1999 interview with The Japan Times, she said that while Genji’s liaisons are typically referred to as seductions, she believed that “It was all rape, not seduction.”

To understand better the terms of the debate, we should first talk about gender relations in the Heian period (794-1185). On one hand, women were allowed to possess, inherit and transfer property, and some of them, like Murasaki Shikibu herself, were capable of great refinement and brilliance. On the other hand, there is no denying that Heian society was ruled by men. They were the ones who studied Chinese and engaged in ‘serious’ subjects like moral philosophy and statecraft. They enjoyed both a public and a private existence, while a lady rarely travelled and lived her life carefully hidden from view in inner rooms. She might not allow a female relative, let alone an unrelated male, to have an unhindered view of her.

The main difference from laws of today is that in the Heian period polygamy was allowed among the aristocrats on a limited basis. Theoretically, noblemen could only have one wife, but, in practice, they had on average two to three, though there seemed to be a hierarchy inside this sort of small harem with all the problems and sometimes tragic consequences one can imagine. Indeed, according to some commentators, ladies in Heian-period society must have endured immense inner suffering despite their outward appearance of happiness.

One prominent voice in this respect is Komashaku Kimi, a modern literature researcher who critically reread The Tale of Genji from a feminist perspective and presented her findings in an essay titled “A Feminist Reinterpretation of The Tale of Genji: Genji and Murasaki” (U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal. English Supplement, No. 5, 1993).

Komashaku points out that in the novel both Genji’s mother and Lady Murasaki’s mother die from psychological disorders brought on by the complex relationships inherent in polygamous marriages. Our Shining Prince himself is no exception: he marries one woman when he is only twelve, then kidnaps Lady Murasaki when she is just a child, keeping her as an unofficial wife, and finally marries the so-called Third Princess, which causes Murasaki such grief that she eventually dies.

More generally, Komashaku argues that Murasaki Shikibu, the novel’s author, believed that women’s misery stemmed from men’s thoughtless philandering and those women, not Genji, are the story’s real protagonists.

On the other side of the fence we have several people who point out that The Tale of Genji is, after all, a product of its time. Among them is Royall Tyler, a British scholar and writer whose 2003 translation of Shikibu’s novel gathered much praise.

In an essay titled “Marriage, Rank and Rape in The Tale of Genji” (Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context, Issue 7, March 2002), he discusses the significance of social rank in gender and sexual relations, arguing that in the Heian period, “forced sexual intercourse has a significance unimaginable in the contemporary world”. He also adds that gender relations in The Tale of Genji “are humane in tone” and “There is no trace of physical violence against women,” to which one could reply that there is no trace of explicit sex scenes either, for that matter. That does not mean, of course, that sex does not happen a lot throughout the story.

As mentioned above, the most controversial aspect of gender relations in The Tale of Genji is rape. The victim of rape is forced into sexual intercourse without her consent, and Tyler readily admits that indeed, rape does happen in the tale. However, he adds that “An attentive reading of the tale shows that no young woman of good family could decently, on her own initiative, say yes to first intercourse. […] A lady in the tale did not do that, in which she resembled many other respectable ladies in other countries and times.”

In other words, if we are interpreting Tyler’s words correctly, a real lady may actually want to have sex with a man but could not openly say so. That is the case of Oborozukiyo, one of the women on whom Genji forces himself. According to Tyler, her “failure to resist Genji seriously reminds him that, despite her charm, she has unfortunately not been brought up to what he considers the highest standard”.

In order to stress the good intentions of the Heian period’s men, Tyler adds that “a man courting a woman socially worthy of him […] does not in principle take initial intercourse with her lightly. In the tale, such intercourse is typically the beginning of a long-term relationship.” In practical terms, rape is bad, but in the end, a lady can only gain from such an incident.

A model of Murasaki Shikibu at Ishiyama Temple in Otsu, where she is said to have written The Tale of Genji. / Eric Rechsteiner for Zoom Japan

Let’s consider the case of another lady, Suetsumuhana. She has lost her father and is in dire straits. According to Tyler, when Genji adds her to his sexual trophies, “her house [is] slowly collapsing around her”. Being a real lady, she resists Genji’s advances, so the poor chap, Tyler continues, “has no choice but to proceed without her consent”. However, “His decisiveness saves her life not once but twice. As soon as the act of sharing her intimacy […] has committed him to her, he has her house and grounds redone and supplies her and her household with all that she needs.” Tyler concludes that “She literally owes him everything.” We could go on; there are many cases of forced sex in the novel. However, we will focus on the central episode: the relationship between Genji and Lady Murasaki.

Murasaki is about ten when Genji, then 17, discovers her. He immediately wants her. However, her grandmother thinks that she is too young and Genji should wait a few years to propose. Murasaki’s mother is dead while her father, a prince, is still alive. Unfortunately, her mother was not the prince’s legal wife. He had an official wife who, due to the toxic environment created by polygamy as I described earlier, harboured intense animosity toward Murasaki’s mother and the child. For this reason, Murasaki’s father has never dared to acknowledge her daughter let alone bring her home out of concern for the treatment she would endure.

Although Murasaki’s grandmother has made it clear that she is off-limits for the time being, Genji manages to get access to the place where she is staying. His intrusion into the child’s bedroom terrifies her, making her tremble with fear. However, Genji finds the girl’s frightened reaction appealing and charming.

Eventually, he carries her away. Komashaku points out that “Although Genji is commonly regarded as a kind and good-hearted hero, we can see in the cases of Yugao [another of his ‘conquests’] and Murasaki that he abducts women by force.” Even Tyler admits that what Genji does is outrageous. However, he quickly adds, “does it harm Murasaki? Considering the realities of her life and her prospects, the answer is no, on the contrary. At her father’s house, she would be […] no more than an unwanted stepchild, a sort of Cinderella.”

Now living at Genji’s palace, Murasaki is treated with “unfailing tact and respect” (Tyler’s words). Even though they sleep together every night, he avoids putting his hands on her. In the meantime, she grows up. Then, when Murasaki is about 14, Genji’s first wife dies, and he begins to view the girl differently. He initially tries to subtly convey to her what he wants from her. Maybe she is just a really naive girl, or maybe all she sees in him is a father figure and finds having sex with him repulsive. Whatever the reason, Murasaki does not seem to understand his intentions. So he takes her by force.

Here is where interpretations of Murasaki’s behaviour differ. Tyler reiterates his opinion that a real lady neither willingly accepts an offer of sex (she is a lady, after all) nor can she refuse (it would be too embarrassing for Genji). So she feigns ignorance. And Genji sees her behaviour as tacit acceptance.

Komashaku’s interpretation is somewhat similar though her overall judgement is much bleaker: “Even if she could fight back,” she writes, “any forceful action by her was condemned as blemishing her femininity. Thus, women’s reactions were restricted to the posture of ‘endurance’ or ‘grief’.”

According to Tyler, “There is no reason to believe that Genji is wrong by the standards of his time. He seems even to have been unusually patient. […] The experience is inevitable, but once it is over, it is over.” Yes, Tyler admits, it’s true that “Murasaki remains furious with him for some time after, but her anger passes.” And anyway, is losing her virginity in such circumstances all that important when life will bring her “great happiness; and in the end it will lift her, for the reader, to a height of grandeur beyond anything her yes or no could have achieved”.

Komashaku’s judgement is more scathing: “Murasaki’s resistance arouses no guilt in Genji, who believes that he is doing her a favour by supporting and marrying her. From a woman’s point of view, however, what happened is clearly rape.” She also highlights the fact that Murasaki “remains hostile toward Genji […] She has stopped looking Genji in the eye, refusing to warm to him even when he approaches her in a playful manner. In a sudden transformation from her previous self, Murasaki seems withdrawn and stricken by grief.”

Fast forward eighteen years (during which the Shining Prince has continued his philandering), and when Genji is 40 years old and Murasaki 32, he takes the Third Princess of the retired emperor Suzaku as his principal wife. Murasaki might be the love of his life but, legally, she is just a quasi-wife (for complex reasons, they could not be formally married).

This new marriage deals Murasaki a tremendous blow. Finding sharing the palace with the new wife too painful, she expresses her desire to become a nun. Genji, however, cannot believe that a woman who has enjoyed a life of luxury under his roof could possibly be miserable. Thus, he denies her last wish, keeping her by his side until, slowly consumed by grief, she dies at the age of 43.

After Murasaki’s death, Genji considers retiring to a temple. According to Komashaku, “His subsequent abrupt disappearance from the tale seems too anticlimactic for him to be the true protagonist.” For her, one thing is clear: “Murasaki Shikibu was no longer interested in writing about Genji. […] I cannot think of Genji as the centre of the text. I consider him to have been an instrument for developing stories with the consistent theme of female suffering. […] If this is the case, it is only appropriate that Genji disappears from the text shortly after Murasaki’s death.”

Komashaku and other modern female commentators believe the fact that The Tale of Genji is often seen as being so incredibly romantic is because most research on the subject is the work of male critics who have taken a liking to Genji and his macho approach towards women. One such writer is Ian Buruma who in “The Sensualist”, a 2015 essay that appeared in The New Yorker, presents The Tale of Genji as a book about the art of seduction. Buruma, for instance, writes that “Genji loves all his women in his own way” and “He is devastated by her [Murasaki’s] early death, described in one of the book’s most moving scenes.”

Komashaku finds the scene moving, too, but for very different reasons. Summarizing Genji’s life trajectory, she concludes that he could not be the story’s real protagonist. “If Genji were truly meant to be the leading hero,” she writes, “Murasaki Shikibu probably would not have made him such an impertinent and unsavoury character, a self-absorbed, callous and inconsiderate womanizer. I think Genji’s insensitivity indicates that he had a supporting role, that he functioned as a foil for the elaboration of the stories of the heroines.”

The morning after her abduction by Genji, Murasaki steps onto the verandah of his opulent palace and gazes out over the garden. She is then captivated by “the beautiful screen paintings that decorate the rooms”. However, at the end of this section, the author writes, “It is pitiful that a child comforts herself by looking at the paintings.” According to Komashaku, “rather than celebrating Murasaki’s good fortune, the narrator grieves over the girl’s fate”. Murasaki Shikibu believed that the lives of these women were miserable. And though the tragic fate of several heroines in The Tale of Genji may be just seen as fiction, Komashaku says that Shikibu’s attitude is also evident in her diary, a work that is pervaded by darkness, reflecting the unresolved pain of being a woman.

Whether one judges those women’s fate as fortunate or tragic depends on one’s views on marriage and gender relations, and Heian-period readers may not share Komashaku’s view of Genji as “self-absorbed, callous and inconsiderate”. Indeed, he was incredibly handsome, well-born, talented, and adequately gentle and kind. However, the fact remains that one does not have to be born in the #MeToo age to condemn certain behaviours.

Gianni Simone

To learn more on this topic, check out our other articles :

No140 [FOCUS] Murasaki, a woman of our time

No140 [FOCUS] Experience – A source for innovation

No140 [TRAVEL] An encounter with flying koi carp

Follow us !