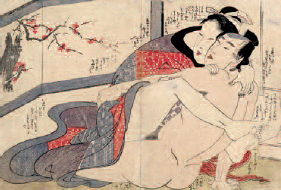

For the first time in 60 years, erotic wood etchings (shunga) are being shown in Tokyo, and have aroused great enthusiasm.

In the old Eisei-Bunko building, which houses a large collection of oriental works of art, around thirty people are queuing impatiently accompanied by the sound of the last cicadas of the summer. Facing them, a guide proclaims loudly that, “There has never been such an exhibition in Japan. Over twenty museums have refused to display it. You will not be disappointed”. As soon as we step inside, we know that our guide was right. It’s impossible to be bored or remain impassive when standing in front of these drawings and wood etchings, illustrating, as they do, a bewildering array of ways that body parts can be rubbed together. This is proved by the fact that all the visitors, whether male or female, young or old, cannot help but make comment in front of every work of art.This exhibition includes over a hundred shunga pieces, erotic drawings and etchings that date back to the Edo period (1603-1868), and has welcomed 30,000 visitors in the first two weeks following its opening on the 19th of September. This greatly exceeded the expectations of the organizers, who initially only anticipated around 15,000 people. The rooms are always full, despite the exhibition staff urging visitors not to linger, but the crowd moves slowly and conversations and laughter break out when someone finds a “thing” that is out of proportion or a certain position that is “ quite impossible”.

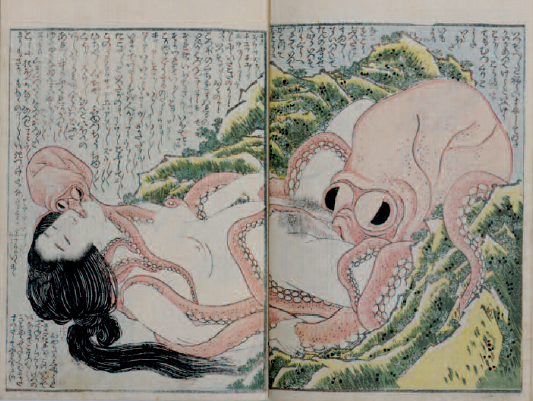

The visitors are wide eyed and marvel to see how the art of love was practised by their ancestors just a few centuries ago. The visitors’ enthusiasm is understandable. Besides the zealous attention to the minutest detail – the artists didn’t shy away from emphasizing the genitals – the skill and care with which the motifs sewn on the kimonos are drawn, as well as the tender and seductive gaze of the intertwined lovers with their disordered hair… all of this bears witness to how Japanese used to enjoy erotic ‘feasts’ in times gone by. Although that is not all there is to shunga… Whether it is an older man lusting for a young rosy-cheeked girl, well-endowed aristocrats or starving farmers, people from every class of society are depicted in the drawings, sometimes coupling with the same sex or even with animals. Nothing is taboo in these etchings, and unlike European drawings from the same period, women are represented having as much pleasure as the men. Sometimes women are even shown masturbating. This panorama of the society and sexuality of the time is so aesthetically accomplished that it would have inspired Michel Foucault – had he been born in Japan – to write a book of several hundred pages. Nevertheless, these wood etchings have been censored throughout their existence. This may seem surprising, but it is the first time that Japan has dedicated an exhibition to shunga, and the road that led to it was full of pitfalls. Uragami Mitsuru, one of the principal members of the organizing committee, had to knock on the doors of over twenty museums before finding one happy to host the exhibition. “For the record, you should know that we weren’t able to find any partners to support us,” laughs this internationally renowned collector, a shunga expert who had to finance the exhibition himself. So why have people been so reluctant? To answer this question it is necessary to retrace the archipelago’s modern history. The censorship that these once popular and widespread etchings and drawings from the Edo period attracted, stems from the country’s westernisation, a path adopted by the Meiji government at the end of the 19th century. This government put an end to the Tokugawa feudal regime in 1868 and tried to turn their country into a modern western nation. To achieve this, they meticulously copied the French and German legal systems, which included laws on obscenity. At the same time, the christian concept of love was introduced into Japan, where native ideas about sexuality were very different.

Together with the idea of “modernity”, chaste western love gained the upper hand over more joyous eastern love, that was soon downgraded to the status of obscenity. The government proceeded to hunt down shunga, these drawings that showed too much of the “shameless” and “non-catholic” parts of old Japanese society. Over a century has gone by, but the same shameful image still haunts these etchings. “It was unthinkable to do any research on these works until the middle of the 90s. One would have risked being expelled from academia,” remembers Hayakawa Monta, a shunga expert and emeritus professor at the Interntional Centre for Research on Japanese Studies. The delay in academic studies has allowed for clichés of shunga being “vulgar and grotesque” to proliferate.

So, “CEOs and museum managers refused to organize this exhibition for fear that their institution’s image would become sullied by these clichés,” complains Uragami Mitsuru, adding with much sarcasm that “Those who think these clichés are true are people who have never actually seen shunga. How can they know whether its vulgar or not if they know nothing about it?” To avoid criticism, the organizers decided that those under 18 were not allowed access to the exhibition, but they point out with irony that nowadays a 15 year old teenager can easily buy porn magazines from one of Japans countless convenience stores. Despite all these hurdles, the exhibition was still able to take place, and the main reason for this is that the taboo on these drawings is gradually disappearing.

The first step was the exhibition “Sex and pleasure in Japanese art” that was organized by the British Museum in 2013. It ended at the start of 2014 after nearly 90,000 visitors in just three months – double the number expected – and was much praised by the British media. “This art is sexy… it’s lush lines and fiery colours are truly the door to alternative wisdom,” concluded Jonathan Jones, art critic for The Guardian. This success was a real turning point in Japan for those in the struggle to have the importance of shunga recognized. Those Japanese who were worried about their image in the west, started to look at shunga in a different light. In addition, recent national crises of conscience on questions of sex, such as the acknowledgement of gay rights and the arrest of an artist who created sculptures in the form of vaginas, also worked in favour of shunga. Many Japanese newspapers and magazines dedicated articles to this exhibition, as though they were celebrating the return of these etchings to their home country. Uragami Mitsuru, who visits the museum two or three times a week to gage public enthusiasm, reminds us that he was hoping to “change the collective conscience with this exhibition, which is playing a pioneering role”. The exhibition will continue until the 23rd of December, but the gamble already seems to have paid off.

Yagishita Yuta

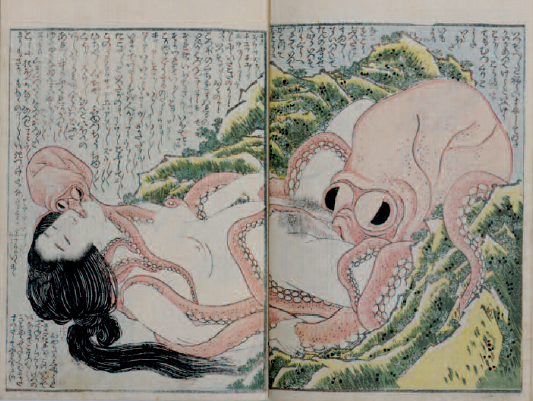

Picture: Hokusai, Diver and two octopuses, from the Young Pines album (Kinoe no komatsu), 1814.