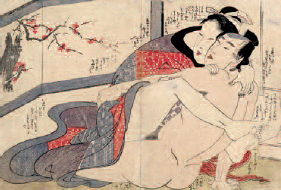

Japanese eroticism is the source of many fantasies. From the 17th to the 19th century, shunga enthralled Western audiences. This beautiful exhibition tells their story.

Japanese eroticism is the source of many fantasies. From the 17th to the 19th century, shunga enthralled Western audiences. This beautiful exhibition tells their story.

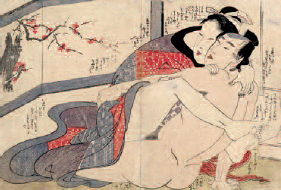

The word shunga, “spring pictures”, gathers together all kinds of erotic imagery, including books, scrolls and engravings. It can also be used to describe the genres of makura-e, “pillow pictures”, or waraie, “laughing pictures”. Most commonly, shunga are prints made using xylography (wood cuts), a technique that has existed in Japan since the 8th century. The production of shunga developed in Japan between the 17th and the 19th centuries, mainly during the Edo period (1615-1867). Around this time a pleasure district developed in Edo (the former name for Tokyo) called Yoshiwara, which allowed temporary escape from a strictly hierarchical society. It was this district of “green houses” that partly inspired engravers of erotic woodcuts, aiding this escape with their humorous and subjective carnal depictions. The first shunga appeared in the form of books in Kyoto, at the end of the 1650s, and the first erotic book to be signed was by Hishikawa Moronobu in 1672 He became the first sublime master of ukiyo-e, “pictures of the floating world” or “paintings of a world passing by”, whose goal is to satisfy pleasures, drink and have fun. The images represent love scenes in everyday life with courtesans and their customers, couples both young and old, domestic servants, bourgeois married couples or aristocrats and animals, with special attention paid to the depiction of genitals. The artist makes the intimate parts of the body stand out by playing with the decor: the curtains, loincloths and petticoats with their patterns that highlight the pale naked bodies and the contours of the bodies and sexual organs accentuated by the deepest of black backgrounds.

The scenes often contain voyeurs in the form of adults or children, even animals, whose facial expressions reveal their reaction when watching sexual acts and who even sometimes imitate them. We ourselves are also peeping Toms, especially when the woman in the painting seems to be staring out at us during her carnal act, maybe as a provocation or an invitation. However, the values promoted in shunga are generally positive towards sexual pleasure for all the participants: for instance, in one memorable colour print from the series “Erotic Illustrations for the Twelve Months” c. 1788 by Katsukawa Shuncho (who worked from the 1760s to the 1790s), a husband and wife enjoy lovemaking at a window in mid-summer to the call of a cuckoo. Sometimes it is a gang-bang or a rape scene, the rapist often identifiable by how ugly or hairy he is, and often considered to be from a lower social class. Most of these scenes depict heterosexual couples, a man with several women or more rarely one woman and two men. Nevertheless, homosexual scenes do exist, either men or women, but they are very much rarer. Male erotic scenes were more usual during the Edo period, in which men with a large age gap are often represented. The passive young man (wakashu) is not yet an adult and submits to his elder (nenja). As for women, they use substitutes such as dildos (harikata) attached to a belt. Prior to the 17th century the erotic engravings were signed with pseudonyms due to censorship but this decreased by the end of the 17th century. During the second half of the 18th century, shunga production grew in all its forms. Nevertheless, very few works have survived. The forms shunga took varied at different periods according to the wishes of publishers and artists but the demand for erotic engravings seems to have been constant throughout the genre’s development from black and white (Sumizuri-e) to using colours, differing formats and materials. Production increased due to the demand from the wealthy chonin (merchant class) and these works related to urban life. Shunga is such a specialized form of art that the British Museum is dedicating a beautiful exhibition to it. The exhibition explores key questions about what shunga is, how it was circulated and to whom, and why it was produced. In particular it begins to establish the social and cultural contexts for sex art in Japan and aims to reaffirm the importance of shunga in Japanese art history. The exhibition is drawn from collections in the UK, Japan, Europe and the USA and will feature some 170 works including paintings, sets of prints and illustrated books with text.

Odaira Namihei