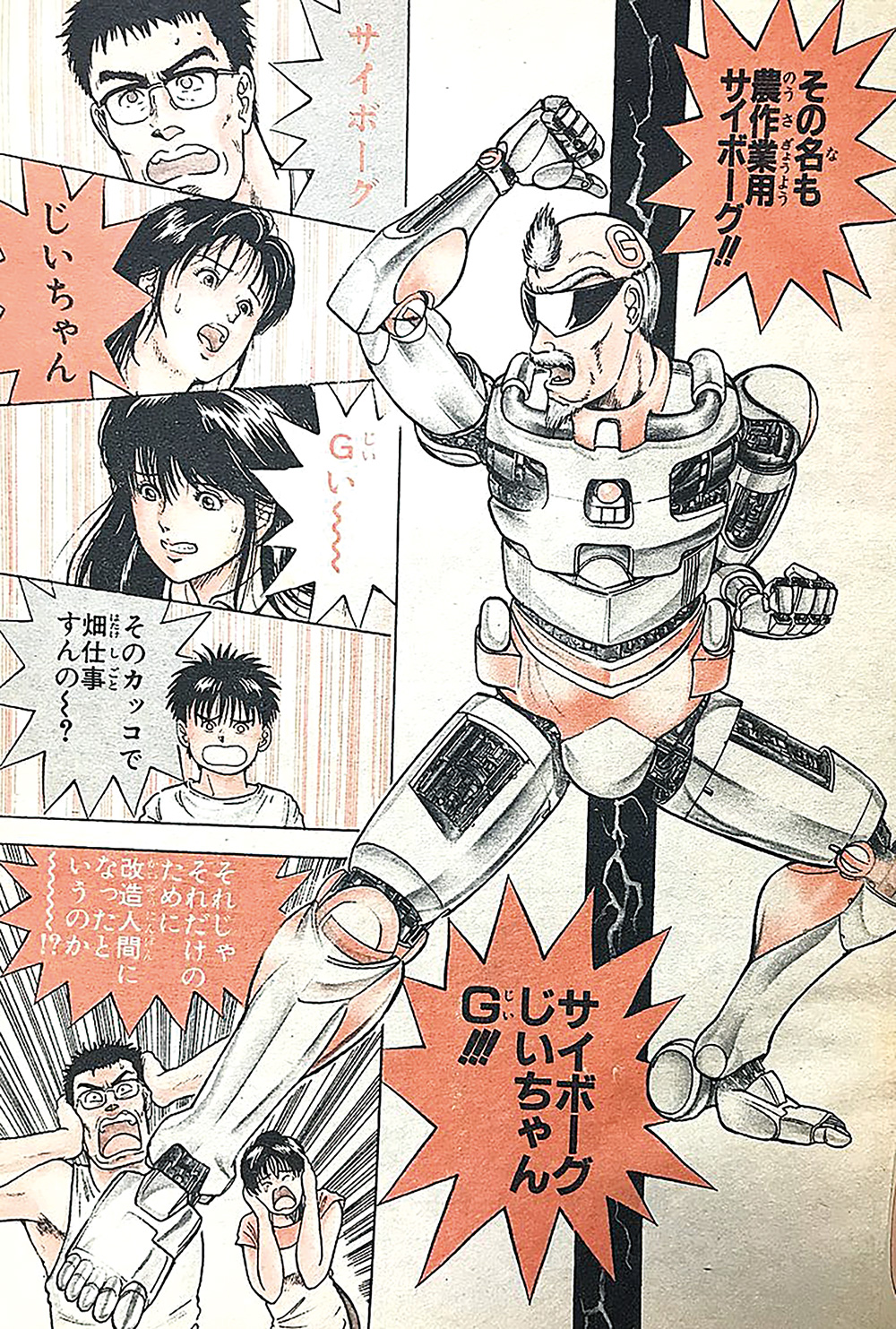

Cyborg Jiichan G published in 1989 by ObaTa Takeshi under the pseudonym KOBATAKE Ken.

For some time now, manga stories about elderly people have been very successful.

comics may be still be considered a young art form for young readers, especially in the West, but a recent trend in Japan shows that there is space and interest for a different kind of manga, that of stories about the elderly. The reason for the rapid growth of this genre is easy to understand: Japan’s population is rapidly ageing. According to the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, 27.7% of Japanese are older than 65, up from 21.5% just a decade ago, and households headed by people aged 65 or older will account for 44.2% by 2040.

Though older characters have always been part of Japanese comics and animation, they have traditionally played a secondary role such as a loving grandma, somebody needing nursing care, or a venerable sage. Typical examples are Otose, the seemingly harsh landlady with a heart of gold in Gintama or Nirasaki, the grumpy farmer in HOSODA Mamoru’s Wolf Children who teaches Hana everything she needs to know about growing vegetables. In MIYAZAKI Hayao’s My Neighbour Totoro, Obaasan is Kanta’s kindly granny who sometimes looks after Satsuki and Mei while SARUTOBI Hiruzen is the wise Hokage who takes care of Naruto. Even zeniba and Yubaba, the two powerful witches who make such an impression in Spirited Away, are only there to either make life hard or easy for Chihiro.

In other words, elderly characters are usually there to support and advise (more rarely to fight) the protagonists – who are always young, like many of the readers – and lend their wisdom and experience to help them grow into strong and responsible adults.

However, things have changed in the last five years, and the brand-new elderly characters who are taking the manga world by storm have been upgraded to protagonists. No longer left in the background, they take their life in their hands, often struggling to make difficult decisions, while making new friends and even rediscovering the joys of sex.

One of the reasons for manga’s sustained success through the decades is the industry’s openness and eagerness to embrace and explore new ideas and trends. Virtually no topic is deemed too strange or uncommercial, from golf, cooking or gambling to office and prison life, and even a quick visit to a Japanese bookshop reveals the range and depth of manga stories. It’s not by chance that, according to the Research Institute for Publications, the Japanese comic industry, both print and digital, grossed 430 billion yen in 2017.

Always looking for new subjects – or a way to approach old ones in a different way – publishers have realised that old is cool, and are now busy exploiting the new genre. In fact, eight of the 11 most popular works with elderly protagonists are pretty new, having been published for the first time since 2014.

Though all the manga featured in this article belong in this category, not all the titles look the same, and the stories can be roughly divided into three distinct approaches. Let’s look at a few of them.

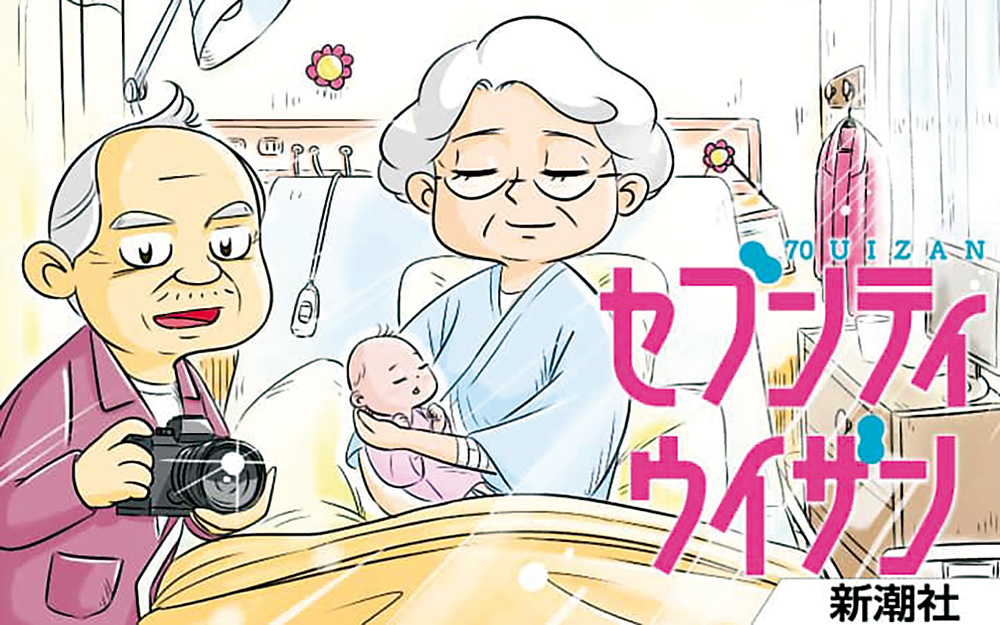

Becoming parents in your 70s is the subject of this series created by TimE Ryosuke and published by Shinchosha.

Fantasy

The first group of manga starring the elderly predates the recent boom and includes typical shonen and seinen manga fare for boys. Jiji metal jacket (1990), for instance, is about a group of pensioners who finally get to do what they had missed out on in their youth: create a rock band. They may live in traditional wooden- and-tatami houses and drink bitter green tea, but the first thing they do in the morning is plug in their electric guitars and blast a few loud chords in their sleepy neighbourhood before putting makeup on their wrinkled faces and getting on stage. This is mostly a gag manga (comedy manga) and carefully avoids any hint of real-life issues. One of the two artists involved in this manga, by the way, has recently turned his interest to more elderly-like subjects with a new comedy mini-series called Hiru no sentozake (Sunshine Sento-Sake) in which the protagonist indulges in drinking booze inside public baths. TORIYAMA Akira is internationally known for such works as Dragon Ball and Dr Slump, but in the summer of 2000 he came up with a short story called Sand Land that was later translated into several languages and was even published in America in Shonen Jump’s English edition. The story’s trio of lead characters consists of a young demon and two elderly men. Rao, for instance, is a former general on a mission to fight the tyrannical king and bring water back to his land, which years of wars and natural disasters have turned into a desert.

Another famous comic artist who has used elderly characters in a bizarrely funny way is OBATA Takeshi. OBATA is the author of such international hits as Death Note and Bakuman, but his first published work (a 31-episode story that came out in 1989) is Cyborg Jiichan G (Cyborg Grandpa G). It is about a farmercum- genius scientist who becomes the titular cyborg in order to revolutionise agriculture and fight the big companies that want to control the world. While working on his grandiose plans, the super-grandpa even finds the time to save an old lady from being killed by a bus, exterminate the crows that are after his crops, and battle against the megalomaniac village headman. OBATA, still a teenager when he penned this story, is already at the top of his game, especially in terms of artistic maturity. The plot itself is definitely over the top and extremely silly, but it’s an exciting tale full of humour.

On the grannies’ front, the stories may be less violent but they are certainly on a par with the grandpas as far as quirkiness is concerned. Take, for example, Obaachan wa idol (My grandma is an idol) by KIKUCHIKumiko. While the events are narrated by a high school girl, the real protagonist is her grandmother, a haughty 70-yearold lady who one day makes a surprise visit to her TV producer son. While checking out the TV studio unsupervised and touching all the machines, grandma is electrocuted. She’s taken to hospital and miraculously survives an operation, but the huge electric shock has changed and revitalised her cells and, in typical manga fashion, the old lady is transformed into a beautiful girl. Grandma’s – and her family’s – life is turned upside down as scores of high school boys fall in love with her, and she’s even scouted by a talent agent and becomes an idol.

In short, the senior citizens in these manga are anything but common people. They do extraordinary things, and the surprise element is what makes the story interesting. The message these manga convey is that the life of the over- 60s is eminently boring and they are only acceptable when they become superheroes.

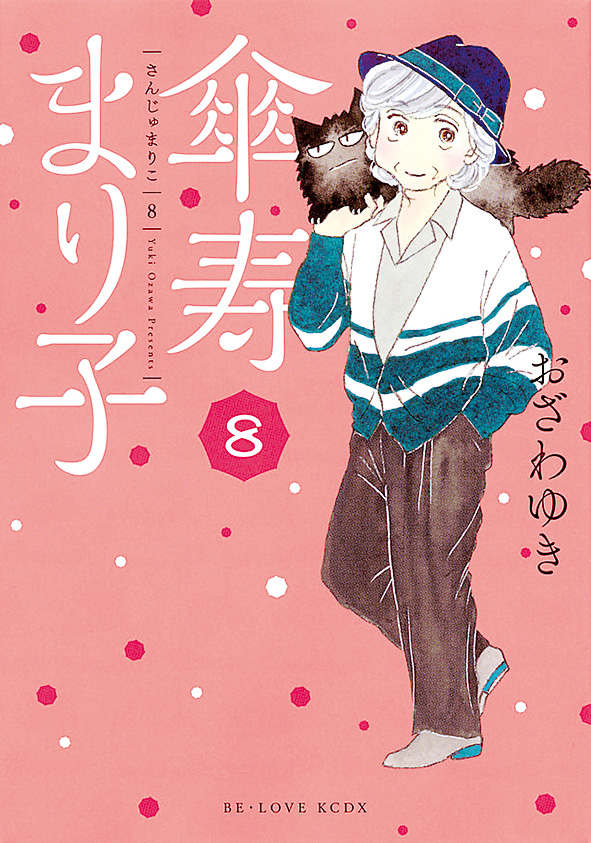

The adventures of mariko, aged 80, enchanted a great many people across the archipelago.

Between fantasy and reality

Even the second group we are going to introduce uses fantasy to attract readers. However, they manage to touch upon some of the real-life problems the elderly have to contend with. Seventy uizan (First child at 70) by TIME Ryosuke features a couple who become parents in their old age. One day the 70-year-old wife goes to the doctor because she feels something is wrong, but to her great surprise she’s told she’s just pregnant. At first the bewildered couple doesn’t know what to do, but eventually they decide to have the child and embark on this new and unexpected adventure that promises to make them feel young again.

IMAI Tetsuya’s Alice & Zoroku has been a series since 2012, and in 2013 won the Japan Media Arts Festival’s New Face Award. Mixing Sci-Fi and family drama, this is the story of Sana, an orphan girl with supernatural powers who is being studied at a secret research facility until she decides to escape. She eventually crosses paths with zoroku, a grumpy old man who eventually takes Sana into his home. The odd couple slowly grows close while evading the research facility and dealing with Sana’s difficult time adapting to the outside world.

OKU Hiroya is the author of the immensely popular Gantz, and his Inuyashiki resembles OBATA’s Cyborg Jiichan G, albeit on a more serious and apocalyptic level. In fact Inuyashiki is the name of an ageing and ill man who is transformed into an unstoppable battle machine after aliens accidentally destroy his body. However, the similarities between the two manga stop here as Inuyashiki decides to use his incredibly powerful mechanical body to fight crime and heal those with incurable diseases. Curiously enough, the story begins like KUROSAWA Akira’s Ikiru, as the protagonist – an employee who mindlessly lives out his boring life – is diagnosed with stomach cancer and given three months to live. Indeed, shi-fi violence aside, the whole story is about a man who, given a second chance, chooses to do something good and meaningful and, in the process, regains his dignity and the love and respect of his once estranged family.

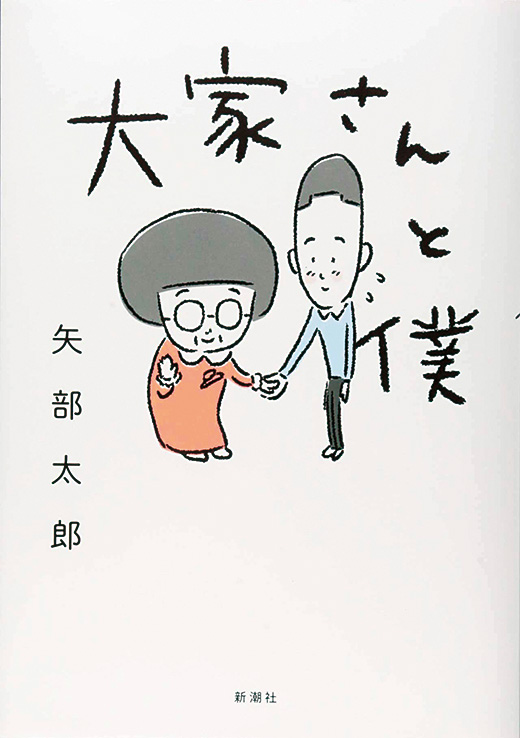

in 2018, Yabe Taro won the prestigious Tezuka Osamu Prize for his collection Oya-san to Boku.

Reality

The last group of manga is also the most interesting because it includes stories that tackle elderly people’s real-life problems and present a detailed portrait of current Japanese society. One of the more interesting titles is TSURUTANI Kaori’s Metamorphoze no Engawa (Veranda Metamorphosis), the touching story of how a septuagenarian widow and a geeky teenage girl become friends.

One of the most popular examples of this manga new wave featuring elderly main characters is OzAWA Yuki’s Sanju Mariko, which has sold more than a half-million copies, both print and digital, since its debut in 2016. Sanju is a traditional way to say “80 years old”, Mariko’s age. She’s a widow and writer who lives with her son, his wife and extended family including her great-grandchild. Sharing the place with them proves increasingly difficult as she feels increasingly lonely and alienated. She reaches a point when she begins to wonder whether her son and daughter-in-law are hoping that she’ll die soon. In the end, it’s a disagreement over plans to rebuild the house that prompts her to leave a place where she doesn’t feel welcome anymore.

From the beginning, Mariko’s life is far from easy. Though she’s healthy and economically independent, she finds it difficult to secure an apartment and briefly becomes an “internet cafe refugee”, joining other people with no fixed abode. Throughout the story, Mariko’s mood constantly swings between happiness and sadness. On the one hand, she actively pursues new challenges, excited by having regained her freedom and even being able to fall in love again. On the other, though, she’s afraid of dying alone, like her friend, and has to face all the big and small problems of daily life.

If Mariko’s story has its light moments and an overall sunny take on old age, SAIKI Mako’s Tasukeaitai: Rogo hatan no oya, karoshi rain no ko (A wish for mutual help: Parents broken after retirement, offspring on the verge of death from overwork) has a much bleaker take on post-retirement life. The 70-something married couple at the centre of this story seems to be enjoying life, between gardening and karaoke, until the husband suffers a stroke and finds himself in need of nursing care. As a result, both the couple and their children have to answer some tough questions besides having to shoulder a heavy financial burden.

SAIKI’s story deals with issues that are often in the pages of the Japanese daily newspapers, namely nursing fatigue – the physical and psychological condition suffered by people in their 40s and 50s who have to nurse their ailing parents without any help from the state. For young people, this problem seems remote – something they hear about, but that doesn’t really concern them – until the same thing happens to them. This manga is more than just a story – it informs the readers of ways to deal with the problem, overcome difficulties, and how to use social security to address financial concerns.

While many of the recent attention-grabbing manga are written by women and feature female protagonists, male artists and characters are also well represented and include a couple of trailblazers that enjoyed a huge success before elderly manga were even considered a genre. Veteran mangaka HIROKANE Kenshi, after achieving stardom with the series Kacho Shima Kosaku (Section chief Shima Kosaku), launched a new series entitled Tasogare Ryuseigun (Like shooting stars at twilight) in 1995. Every volume features the following statement: “In their later years, men and women sometimes find themselves in the glow of love. Their love stories shine like shooting stars in the twilight”. And sure enough, the series features stories of older people who find romance and enjoy racy pleasures in the process. In one typical story, a 70-year-old widower, bored with retirement, takes a part-time job as a company chauffeur. He is assigned to drive a senior vice president – a woman nearing 60 who has never found room for love in her hectic working life. Over time, they develop a warm friendship. One night, the two end up in a love hotel, and after a wild night in bed, they become ardent lovers. The Tasogare Ryuseigun series has been so successful that HIROKANE has published 59 volumes so far (it’s not over yet) and sold millions of copies.

Another male artist with a completely different approach to old age is OKANO Yuichi, who published a comic memoir about his mother, Pekorosu no haha ni ai ni iku (Meet Pekorosu’s mother). OKANO’s manga was originally a series published as a four-panel strip in a local newspaper, and the collected stories were published in book form in 2012. The manga depicts the partly fictional daily diary of a 62-year-old man – a manga artist – dealing with his 89-year-old senile mother with dementia, and like Tasukeaitai… highlights problems around care for the elderly, but in a more gentle, humorous, even poetic way.

The most recent of these comic books created by men is by YABETaro, a 40-year-old comedian who, in 2016, began a series in a literary magazine about his relationship with his landlady – a woman in her late 80s. Oya-san to Boku (The landlady and I) is another keenly observed portrait of a woman who has experienced many ups and downs including divorce at a young age, but manages to keep level-headed and maintain a fundamentally optimistic outlook on life. While living on the second floor of the lady’s house, YABE gets to know her well, and the two develop a warm and personal relationship. YABE’s comic strips were compiled into a book, which was published in 2017 and, a year later, won the prestigious TEZUKA Osamu Cultural Prize in the short story category. It has sold almost half a million copies so far.

The best among the titles we’ve introduced here demonstrate that a sense of humanity lies at the heart of the genre’s success. The readers might be people in their 60s or 70s who have loved manga since they were kids, or young readers worried by society’s progressive ageing, but they all share the same worries and anxieties.

GIANNI SIMONE