A country’s cuisine is of great importance to it, both culturally and economically. Many see its protection and preservation as being of vital importance.

A country’s cuisine is of great importance to it, both culturally and economically. Many see its protection and preservation as being of vital importance.

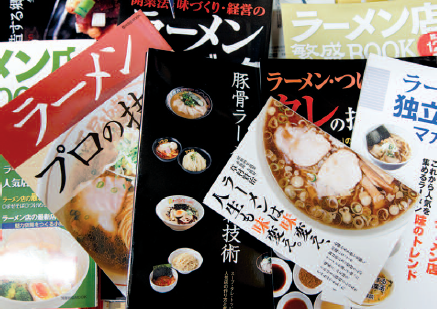

During the meeting of Unesco’s intergovernmental committee held in Bakou from the 2nd until the 7th of December, Japanese authorities hope to have Japanese cuisine (washoku) registered as an Intangible Cultural Heritage. By taking advantage of the international enthusiasm for sushi and other traditional dishes such as ramen (Japanese noodles), they hope to be able to use the Unesco label to reinforce a positive image of their country, in much the same way as has been done with manga and animation. At the moment, cuisine is part of the “Cool Japan” policy that was launched in 2000. Another objective of obtaining the status is to keep an eye on the quality of products and the conservation of Japanese culinary know-how. According to the Ministry of Agriculture, there were 55,000 Japanese restaurants around the world by the end of March 2013, compared to 24,000 in 2006. Furthermore, there seems to be no reason for this incredible growth to halt; a study carried out by Jetro, the Japan External Trade Organization showed that in 7 countries (China, Taiwan, Hong kong, South Korea, the United States, France and Italy) Japanese cuisine is the foreign food that people most want to eat. From San Francisco to Dubai, customers line up to get a taste of the archipelago’s specialities. In 80-90% of cases the restaurants are owned by non-Japanese chefs, which explains why the government wishes to find ways to preserve traditional know-how and techniques. Having a Unesco heritage label is also a guarantee for Japan to take the lead in a market that has been estimated will reach £380 million by 2020, three times more than it is worth today. Interest in Japanese cuisine emerged in the United States in the 70s, when Americans started taking interest in their well-being. Concerned with eating healthy and low calorie food, they turned to raw fish. The first sushi restaurants in the U.S.A. started in California on the west coast and welcomed a clientele of movie stars as well as locals from the middle classes, who were drawn by all the talk about nutritional balance. Bit by bit, the sushi trend spread throughout the country.

In New York dedicated restaurants sprang up like mushrooms to respond to the growing demand. For many, sushi became a way of life and, like many things, what seduces the Americans often crosses the Atlantic to Europe. Unlike manga and animation, which travelled directly from Japan to Europe, Japanese cuisine took a more indirect route. Along its way, sushi was subject to transformation and adaptation. When it was introduced to the United States in the 60s, some people were still hesitant about eating raw fish, so the Japanese cooks invented the California roll, made with avocado and crab, that was closer to local tastes. This speciality was a great success and travelled across the world. Today many restaurants in Paris or London have it on their menus. Other adaptations were made elsewhere, to better fit with local tastes and the ingredients available. For example, sushi bars are everywhere in Sao Paulo, Brazil, a city witch has its own strong Japanese community. According to the Brazilian Bar and Restaurant Association, there are more places offering sushi than local churrascaria, which specialize in meat dishes. In 2012 there were 600 sushi bars, compared to 500 churrascaria, and what is offered is sometimes quite surprising. In imitation of the California roll, mango is often used in sushi as it is cheaper to buy than avocado in Brazil. A restaurant chain in Singapore even copied the idea and now sells them. The list of changes made to traditional sushi is long and it will continue to grow despite the Japanese government’s wish to conserve its fundamental characteristics and traditional culinary techniques. However, cuisine is a living thing that evolves over time and the sushi that the authorities wish to protect has little in common with the sushi found on Edo’s streets during the 19th century. At that time they were equivalent to hamburgers and other fast food snacks. With time the nature of sushi changed and became the symbol of a way of life and a refined style of which Japan is rightly proud. The wish to prescriptively define Japanese cuisine might even be counter-productive. Some may consider it a form of nationalism, at odds with Japan’s efforts to find its place among its neighbours who have become rivals on the international scene.

In support of its application to Unesco, the government has put forward two specific characteristics of its cuisine for consideration. As well as the “social custom” that underlies family and community ties, it insists on the fact that Japanese cuisine depends on “a seasonal diet that is respectful of nature”. The idea to apply for Intangible Cultural Heritage status arose in March 2012, a year after the tsunami and the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear disaster. This event had a very negative impact on food exports from Japan and many countries imposed embargoes. For example, South Korea used to import a lot of Japanese fish but has now banned it. Similar measures still apply in other countries, and these have been of little help to Japanese producers. By being recognized by Unesco, the authorities hope to win back trust faster. That would be good news for the current government, which also hopes to transform Japanese agriculture into a luxury export market as it is unable to compete with the mass production of larger agricultural producing countries. Prime minister Abe Shinzo’s proposition was put forward a few weeks ago during the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) negotiations, the free exchange agreement to which most Japanese farmers are opposed. As well as winning back trust thanks to inclusion on the Unesco list, the authorities also hope to ensure a future for Japan’s agricultural production. The popularity of Japanese cuisine abroad is a commercial opportunity for those Japanese who want to profit by offering products adapted to local tastes. A company called First, benefiting from the Japanese government’s support of the Cool Japan campaign, has begun marketing the Japan Halal Food Project (www.jhfp.jp), the aim of which is aim is to promote Japanese food in Muslim countries. To start with it is targeting the Indonesian market, with its population of 230 million, 70% of which are Muslim. With, the launch of the Cooking Japan website in December, which will offer recipes and advice in Indonesian for making Japanese food, they hope to attract 200,000 monthly visitors during the first three months. Asia is the project’s number one target as it is in this part of the world that there has been a veritable explosion of Japanese restaurants, from 10,000 in 2010 to 27,00 in 2013. Mogi Yusaburo, the CEO of leading soya sauce producer Kikkoman, is also the president of the Organization to Promote Japanese Restaurants Abroad (www.jronet.org). He never misses an opportunity to underline the necessity of valuing true Japanese cuisine and strongly supports the Japanese government’s initiative in trying register it as an Intangible Cultural Heritage. Here is evidence that Japan is ready to fight in defence of its gastronomy.

Odaira Namihei

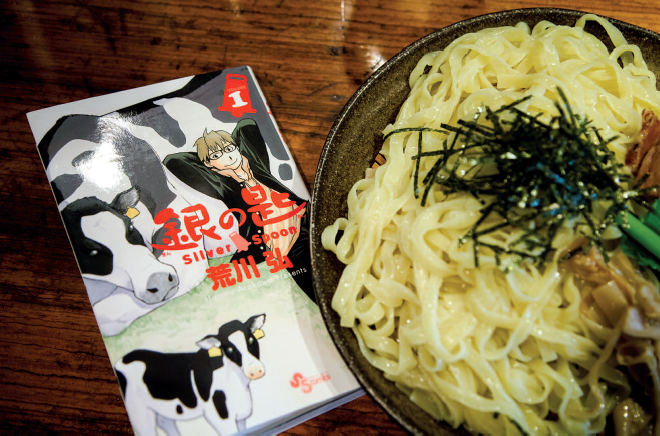

Photo: Men Oh Tokushima Ramen