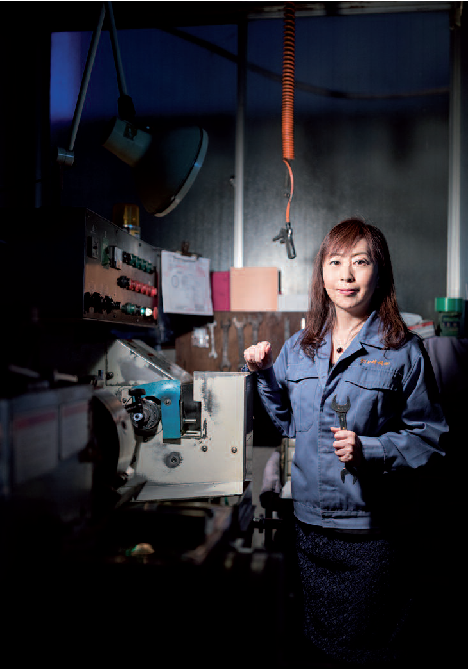

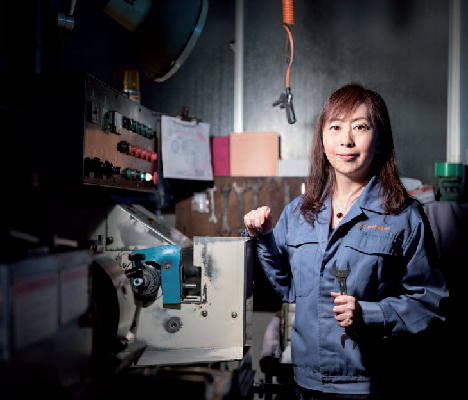

Suwa Takako’s success in a very masculine milieu has set a benchmark for women throughout Japan.

For Suwa Takako, the decision to take her father’s place was practically made for her. It all happened on a cold and rainy evening in April 2004. Suwa, then 32 years old, was called to the hospital. Her father Yasuo, founder and president of Daiya Seiki, a company specializing in the production of measurement machines for cars, had just been admitted to the emergency ward. The doctor told her that it was acute myeloid leukemia and that her father had only a few days left. Takako never really had time to weep about her father’s situation though. At Daiya Seiki, located in Tokyo, about thirty people worked for important clients such as Nissan; it was crucial that her father’s hospitalization did not stop this work. So her priority was to collate all the practical information she could, such as where the bank books and the safe-deposit box code were kept. The doctor’s prognosis was correct and a few days later, Yasuo died. His daughter barely had time to say: “Don’t worry about the company!” He was only 64 and had hoped that Takako would succeed him, but the decision wasn’t an easy one for her, as in many people’s eyes she was just a housewife. “I thought about it for a month,” she recalls. She was already married at the time and didn’t need to earn a living. Furthermore, her husband was about to travel to the US for work. “I wanted to go with him and learn English” she admits. Having already worked as an engineer for two years at Hitachi Automotive Systems, a company making spare car parts, she already knew what it was like to be a female manager in this almost exclusively masculine milieu.

To help make up her mind, she spoke with each and every one of the company’s employees. She asked them: “Would you go on working for the company if I were to become its CEO?” and the oldest employee simply replied: “We want you to take over from Yasuo”. She finally made the decision in May 2004, and became the new head of Daiya Seiki. Thirteen years later, she says she has never regretted that decision. However, Takako didn’t take on her father’s role without introducing some ideas of her own. She knew the company’s strengths and weaknesses and her two years spent at Hitachi had also given her an opportunity to form her own ideas, telling us that “What I learnt from that company, which is much larger than mine, was very useful”. Her father had already asked her to work in the factory, which had given her the opportunity to formulate management plans, meaning she was far from being the mere “born yesterday housewife” that many had thought.

In spite of her experience and insight, her debut was overshadowed by problems with the employees and disagreements with the banks. To top it off, the factory’s balance sheet hadn’t moved since the financial bubble of the 1980s had burst. “We needed to reduce the payroll and cut costs,” she recalls. After many sleepless nights, she decided to take the bull by the horns and sacked five people. Her father could never have done such a thing, due to the company’s family friendly ethos. Though her actions led to feelings of mistrust between her and the team, they helped save the company, and it’s economic outlook improved. “Thanks to Carlos Ghosn’s reforms, the difficult situation for Nissan, one our main clients from my father’s time, improved” she explains. The recovery from this crisis allowed her to refuse a take-over bid that a bank had advised her to accept. The money men had prematurely judged that Takako would not be able to manage the company, and had encouraged her to merge with another firm.

In 2007, Takako switched to the second tranche of her reforms, which involved rejuvenating the team and passing on skills to the younger generation. Since her father’s time, Daiya Seiki had maintained a solid reputation with its customers. The production of the measurement machines they make, essential for the manufacture of cars, requires extreme precision, with some veteran factory employees are capable of hand making some devices to the exact micrometre. “Do you know what that represents? A micrometer is the size of a particle of cigarette smoke. There are only five companies in Japan capable of doing what we do,” she says proudly. At the time, the average age of the team was 53. An ageing workforce and problems of succession are common to many of the machikoba (small urban factories) such as Daiya Seiki, that were created between 1950 and 1960, so to attract younger employees, Takako emphasized Daiya Seiki’s family atmosphere as its “main strength”. She also created an internship and mentoring system for people with no experience, and tried to introduce mediation between the older and younger engineers. She even organized barbecues, to which the employees’ families were invited. She claims that “today our age pyramid is perfect. We’ve recruited twenty people since 2007, which has lowered the average age to 38”. Little by little, her exceptional career has attracted the media, who are on the lookout for a female manager who can act as a figurehead for the intention of Japanese society to break with old habits. In a country where the percentage of women managers remains around 10%, her career is a dream, and in 2012 she received the “Woman of the year” prize awarded by the magazine Nikkei Woman. “I feel responsible for Japanese women who want to work in the same way as men, but can’t. I have to continue being a role-model for them,” she says. Since her award, Suwa Takako has attended around a hundred conferences per year. CEOs of machikoba threatened by international competition and problems of succession are desperate for her advice. “These companies are technologically strong, but they’re not good at communication,” she suggests. “The next decade will be crucial for the transmission of technological skills. These two factors are essential if these companies are to survive,” she adds.

YAGISHITA YUTA

Leave a Reply