To save themselves from having to close down, several businesses have got together to build a bobsleigh.

Tourist brochures often use the word shitamachi (literally low city or “downtown”, i.e. a working-class area) when talking about such popular districts as Asakusa or Nihonbashi. However, the most authentic shitamachi experience one can find nowadays in these places are souvenir shops and pale reproductions of the good old days. In order to find the real shitamachi, one must cross the Sumida River and explore Tokyo’s eastern wards, or go south, towards the border with Kanagawa Prefecture.

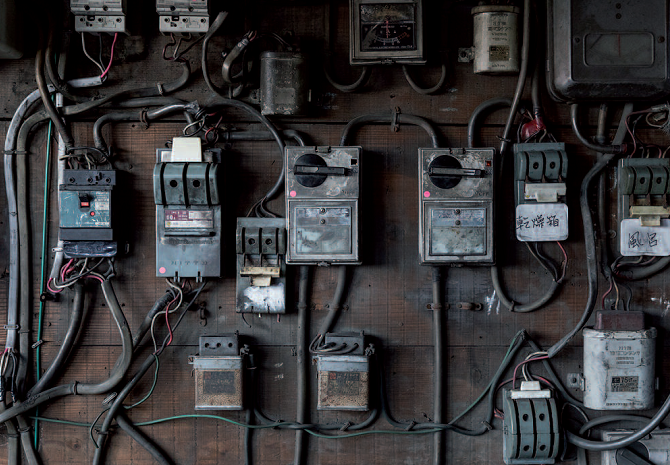

Here lies Ota-ku, Tokyo’s largest ward by area and the third most populous. You will not find many tourist-friendly spots in Ota though. After all, it is mainly known for its manufacturing industry and for having Tokyo’s biggest concentration of machikoba (small factories). The same people both live and work here, so the population is roughly the same during the day and the night.

Ota’s long manufacturing tradition goes back 100 years, to when local fishermen learned how to make metal parts for a now-defunct Imperial Navy shipyard. However, it wasn’t until the 1950s that the ward’s current landscape began to take shape, with hundreds, then thousands of small and medium-sized factories and workshops springing up everywhere and flourishing through the boom years thanks to their technical expertise and obsession with detail.

Unfortunately, the bonanza came to an abrupt end in the early 1990s due to the changing economic situation. Ota’s companies were hit hard again by the 2008 financial crisis and the 2011 disaster in Fukushima, which prompted big companies to subcontract their production to cheaper labour markets abroad. As a result, fewer than 4,000 factories are currently left out of the 10,000 that were still operating during the 1980s.

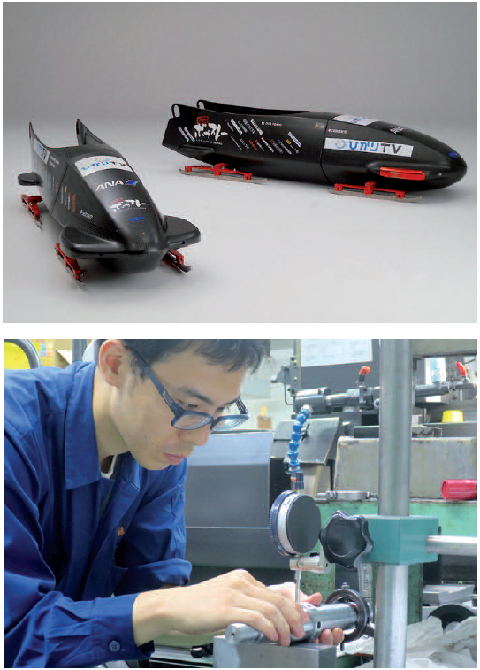

As they say, desperate times call for desperate measures, and that’s what a group of enterprising machikoba must have thought when they decided to embark on a a daring and outlandish project that would rebuild morale and spread the word about Ota’s local industry around the world: building a bobsleigh.

Bobsleighs are like F1 race cars on ice. Building one requires a lot of specialized technical knowledge, the kind of expertise that is developed over many years of trial-and-error and experimentation. Many of the more respected bobsleigh makers are currently based in Europe, including such awe-inspiring names as BMW and Ferrari. As the Shitamachi Bobsleigh Project’s (SBP) chairman Hosogai Shunichi has already said many times during interviews in the last five years, “For the last 25 years the Japanese economy has been in constant decline amid rising labour costs and other problems. At Material Co., Ltd, my company, we were lucky enough to avoid these problems because we have built up technical knowhow, which has allowed us to work in collaboration with both the aerospace and defence industries. However, we were looking for new ways to raise our public image, particularly abroad. Then, one day in 2011 a civil servant in Ota approached me with the idea of building a bobsleigh”.

Hosogai had heard that the Japanese national team had never used a domestically manufactured bobsleigh before. However, the foreign sleighs were a little too big for the Japanese athletes, and the lack of Japanese mechanics meant that nobody was available to fix problems.

“As bobsleighs are not equipped with engines, I realized this was a good opportunity to use our knowhow to develop a new product in cooperation with other local machikoba, without having to ask for help from a major company,” he recalls. “The problem was that nobody had ever built a bobsleigh in Japan before”.

So they borrowed an old German-made bobsleigh from a university in northern Japan and took it apart so see how it was actually made, discovering that about 150 different parts were needed. Hosogai gathered a group of Ota-based machikoba owners and asked them to join the project. “That was in 2011. Unfortunately, because of Fukushima and everything that followed, we didn’t really make any progress during the first year,” he says. “Things started to move in November when around ten companies got together to decide what to do. Then, in May 2012, we called a press conference and were surprised by how many reporters came. The day after, many newspaper front pages were devoted to our challenge”.

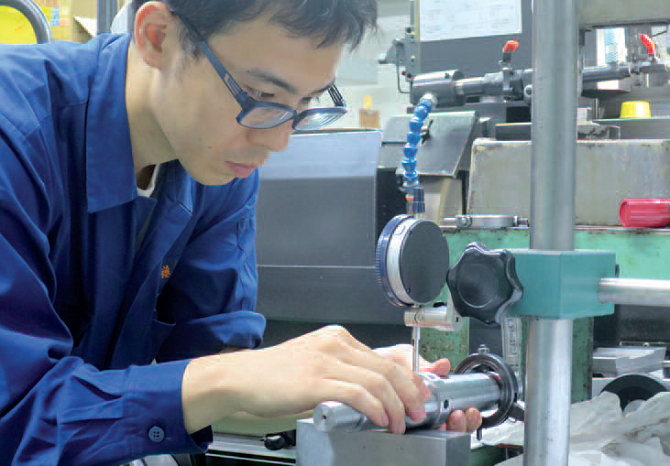

More and more companies kept joining, so many that now the committee is made up of around 100 machikoba. Each company then built sections of the bobsleigh according to their own area of expertise, from metal-cutting and shaving to welding, sheeting, plating, etc. Material, for instance, specializes in aluminium, while at Showa SS Co., Ltd. they use unique proprietary techniques to produce metal prototypes for materials testing. Another SBP member company, Kamijima Netsushori Co., Ltd., uses a metal heating and cooling process by which they are able to enhance its inherent proprieties and make steel many times stronger and longer lasting.

Since all the companies are located in Ota Ward and are very close to each other, each time they encountered a problem they were able to pool their skills and solve it quickly. “I think, at first, many people were afraid of sharing their technology,” Hosogai says. “They also never thought there’d be any financial benefits. But I think it’s only through wide-ranging cooperation like this that we can challenge the world”. In the end, the 150 parts needed to build the bobsleigh were completed in only 10 days. They’re said to be stronger than the German ones, which were used as examples to work from, because they’re shaped from single pieces of steel instead of separate pieces welded together. The cost of the first prototype was 18 million yen, 10 million of which came from the Ota Ward government, while the rest was supplied by Material.

Hosogai is very pleased with the publicity created by the SBP. Machikoba are generally thought to belong to the manufacturing industry, but in his opinion they should consider themselves as part of the service sector instead. “When you think about it, you can have the best technology possible, but if you don’t find someone who is actually interested in what you make, you can’t do any business,” he says. “There’s a saying that technological strength in itself does not bring in any money. In fact, publicity is essential to spread the word about a company’s technological knowhow. Without good promotion and publicity you’re not going to accomplish a lot. That’s one of the reasons why we embarked on the SBP”.

In order to further enhance the project’s public image, the committee had hoped to convince the Japanese national team to use their bobsleigh, but the squad opted for a European-made model both for the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics and the upcoming 2018 Games in PyeongChang. In the end the Jamaican Bobsleigh Federation decided to use the Shitamachi Bobsleigh in their attempt to qualify for next year’s event. If successful, their appearance will mark the 30-year anniversary of their famous Olympic bobsleigh debut, which inspired the Hollywood film Cool Runnings.

The Japanese companies had to make a few changes to accommodate the new team’s needs. While earlier models developed for Japanese athletes had a relatively spacious interior, Jamaican bobsleigh competitors are said to be more focused on reducing air resistance. “Until now people had to adapt to the bobsleigh,” Hosogai says.”We decided to do the opposite and customize our bobsleigh to the athletes using it. So we’re taking a totally different approach”.

Hosogai’s hope of helping Jamaica win an Olympic medal may be a little far-fetched, but he remains convinced that Ota must change in order to survive and prosper. Small Japanese companies lack the capital to expand their business and compete with mass production in countries such as China or Korea. Besides, they need to stop relying on big corporations or the government to lead the way, and instead learn to embrace innovation on their own terms. The only way is to adopt a new strategy and break into more customized, high-end manufacturing, which is currently dominated by countries like Germany and Italy.

Jean Derome

Leave a Reply