The novelist never misses an opportunity to question the way Japan is evolving.

In her work, Kawakami Hiromi looks at what awaits humankind, for better or for worse.

Just like her novels with their vision of a fantasy world, when meeting Kawakami

Hiromi, her tone is both poetic and mysterious.

We interview the novelist who writes with such warmth about people, to question her about the path she’s chosen, and what she thinks about today’s human beings, and those of the future.

What made you want to become a novelist?

Kawakami Hiromi : I started writing when I was a student, as a member of the SF club, when we were creating a literary magazine.

Did you like science fiction beforehand?

k. H.: Sort of… But since there was no literary club to speak of at university, and I was studying science, I chose to join the nearest thing to a literature

club.

What do you like about SF?

k. H.: The world that SF offers is different from our reality. At first glance, what it describes seems unreal. But in that unreal world, how humans behave and all that happens touches on our deepest feelings. That’s what I love about SF. You lived in the uS when you were a child.

Do you have memories of that time?

k. H.: Yes, many. But I don’t really remember what happened when we returned to Japan (laughs). That’s maybe because it was a unique experience. We were there for about three years, between kindergarten and primary school.

Is your writing influenced by your time in America?

k. H.: Yes, certainly. Not only by my American life, but by my whole life. Currently, I’m writing a series of short stories for the magazine Monkey, whose editor-in-chief in M. Shibata Motoyuki. They’re translated into English as Konoatari no hitotachi (Folk from round about).The stories take place in a town in Japan, so they’re very Japanese, but I wrote them while thinking of my life back in the US.

Why do you prefer writing short stories to novels?

k. H.: I like novels, but I feel more fulfilled when writing short stories. It takes a great effort for me to write a novel, whereas when I write an short story, it feels like there are no obstacles.

You feel freer?

k. H.: How can I put it… Yes, there’s more freedom in this genre, without downplaying the freedom that a novel can offer. Though novels can tackle grandiose ideas, I prefer something less imposing, and short stories fit that description.

kamisama 2011 (God Bless You, 2011) was based on a collection of your short stories, to which you added the subject of nuclear power. How did the 2011 earthquake influence your writing?

k. H.: I wrote it two days after the explosion at the nuclear power station. I wanted to do something, anything. But all I could do was watch TV, not knowing what was going to happen. At that time, naturally, many locals left the region,

and if things had got worse, Tokyo would have been uninhabitable for some time, maybe for ever. My intention wasn’t to describe what was going on in Tohoku, but what was happening to me. Until then, I had never really felt that nuclear energy was dangerous, but after the disaster, I realized how horrific it was. I thought to myself: why would anybody create something so abominable? What would happen if there were an accident? How could the story be told? What would be the best way to exp’ress my feelings? I then came up with the idea of a man and a bear in Kamisama, and what would happen if they were forced to live there after a nuclear disaster? I wrote this over a very short period of time.

Okina tori ni sarawarenaiyo, (To protect us from a great bird, not published in English) published in Japan in 2016, describes humankind in the future. The story appears to hinge on the natural disaster that occurred in march 2011.

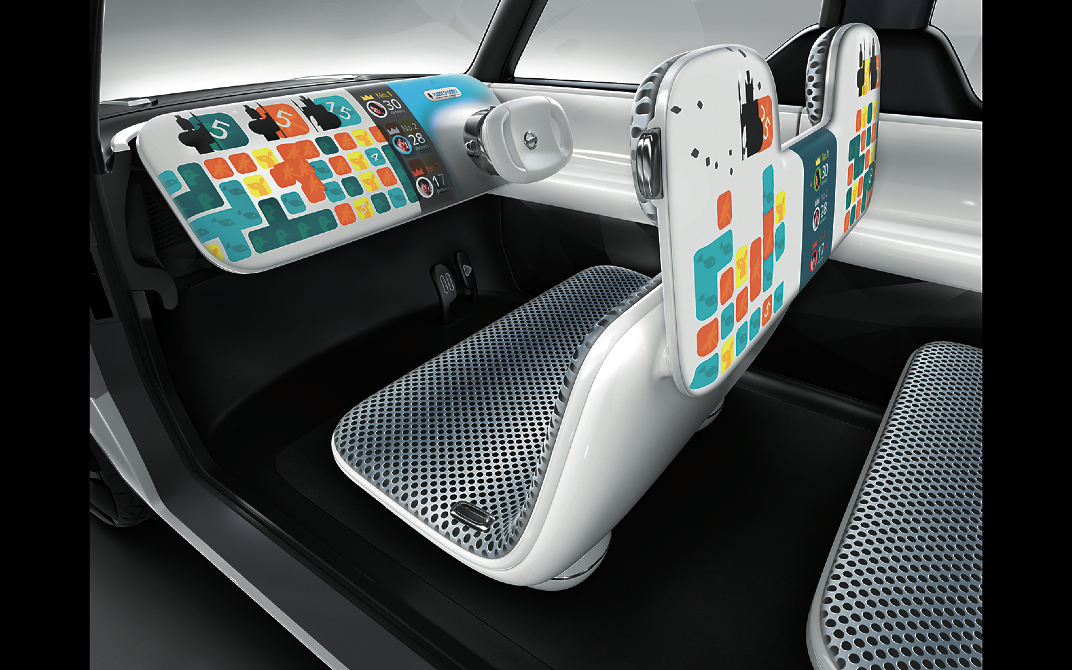

k. H.: Yes, it does. All new technologies are far in advance of human capabilities. I’m not only thinking of nuclear power stations, but also genetic engineering. Once triggered, we lose control over them. Having said that, humankind will fade away one day. That’s its destiny, just as man himself is mortal. These are the two themes I wanted to develop in this novel.

Though it doesn’t seem so alarmist when one reads it.

k. H.: No, it doesn’t. It’s not meant to alarm people. That isn’t my job. However, its inevitable that if the worst happens, nothing can be done. I’m not saying that’s this is the only way. Every novelist has his own role to play: either to sound the alarm, or state clearly that there’s no need to worry! But it would be best to never reach that stage.

You still shed a warm light on humanity in the future.

k. H.: Thank you. Yes, I feel a lot of love for humankind.

What do you find interesting in today’s Japan?

k. H.: I’m very interested in Japanese people. Particularly when you’re abroad, one thinks about what is original about the Japanese, both good and bad. Living in Japan, and reading the papers or watching the news, I don’t stop asking myself this question. I started doing this during the period of the economic bubble (1980-1990). Japan hasn’t stopped changing since I was a child. There haven’t been any really great changes, but the Japanese are constantly updating. It’s very strange. And that’s what I’m interested in currently.

Interview by Hara Satomi

Leave a Reply