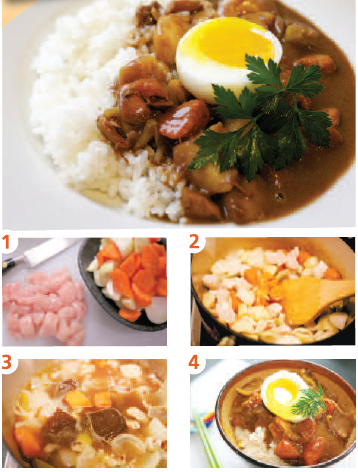

Discovering new flavours is always exciting, but umami will open your eyes to an undiscovered taste.

often ambiguously defined, the term “umami” is seen occasionally, but is perhaps not yet so well known in the west. It was first coined in 1908 by Ikeda Kikunae, a chemist from Tokyo University in Japan. He discovered a particular kind of savoury taste, later understood to come from an amino acid which is found in some ingredients such as asparagus, tomatoes, cheese and meat, but that is most apparent in Japanese dashi – a rich stock made from kelp. To relate this discovery to a term that we are perhaps more familiar with, Ikeda eventually learned to produce the notorious flavour enhancer “MSG”.

The book Umami: The Fifth Taste, written by Michael Anthony, explores the in-depth wonder of this seldom recognised flavour category, interviewing the world’s most renowned chefs about the significance of umami in the culinary world. According to the book, umami is known to be the fifth taste after “sweet” “sour” “salty” and “bitter”. It is a subtle taste, almost undetectable and usually overshadowed by other, bolder flavours. The key aspect of umami is, however, its essential role in harmonizing with the other basic flavours and acting as a catalyst to bring out the characteristic taste in many foods.

Moreover, the ability to detect basic tastes is an essential biological function. The idea that taste is not just a source of enjoyment, but a set of signals that direct us to satisfy the body’s needs or to protect it from harmful substances, is generally accepted based on a large body of physiological and nutritional studies. Take the four more wellknown tastes for instance: sweetness is a signal we are getting energy from sugar; sourness is a sign of organic acids in unripe fruit and rotting foods and tells us to avoid these in excess; the saltiness of minerals is necessary to maintain the balance of bodily fluids and the bitterness from alkaloids enables us to avoid harmful substances. Recent studies show that umami signals to the body that we have ingested protein, and according to Anthony, it also facilitates the digestion of that protein by promoting the secretion of saliva and digestive juices.

Indeed, understanding our preferences towards the flavours in our foods is crucial to recognizing our motivations for food choices, and ultimately for ensuring a healthy diet. This applies particularly to the role played by umami flavours since, unlike sugars and fats, they do not contribute to obesity or other health problems.

Umami, the “savoury” taste, is unique in its distinctive form, and it has now been recognised by scientists as something in its own right and not just a combination of the four traditionally defined taste receptors. As an avid fan of Japanese food, I look forward to seeing the potential long-term formulation and development of newly discovered umami tastes that are yet to be understood.

Leave a Reply