The Liverpool band’s only tour of Japan was both a headache and a historic moment.

More than 50 years after they broke up, the Beatles remain one of the most popular bands ever, and Japan

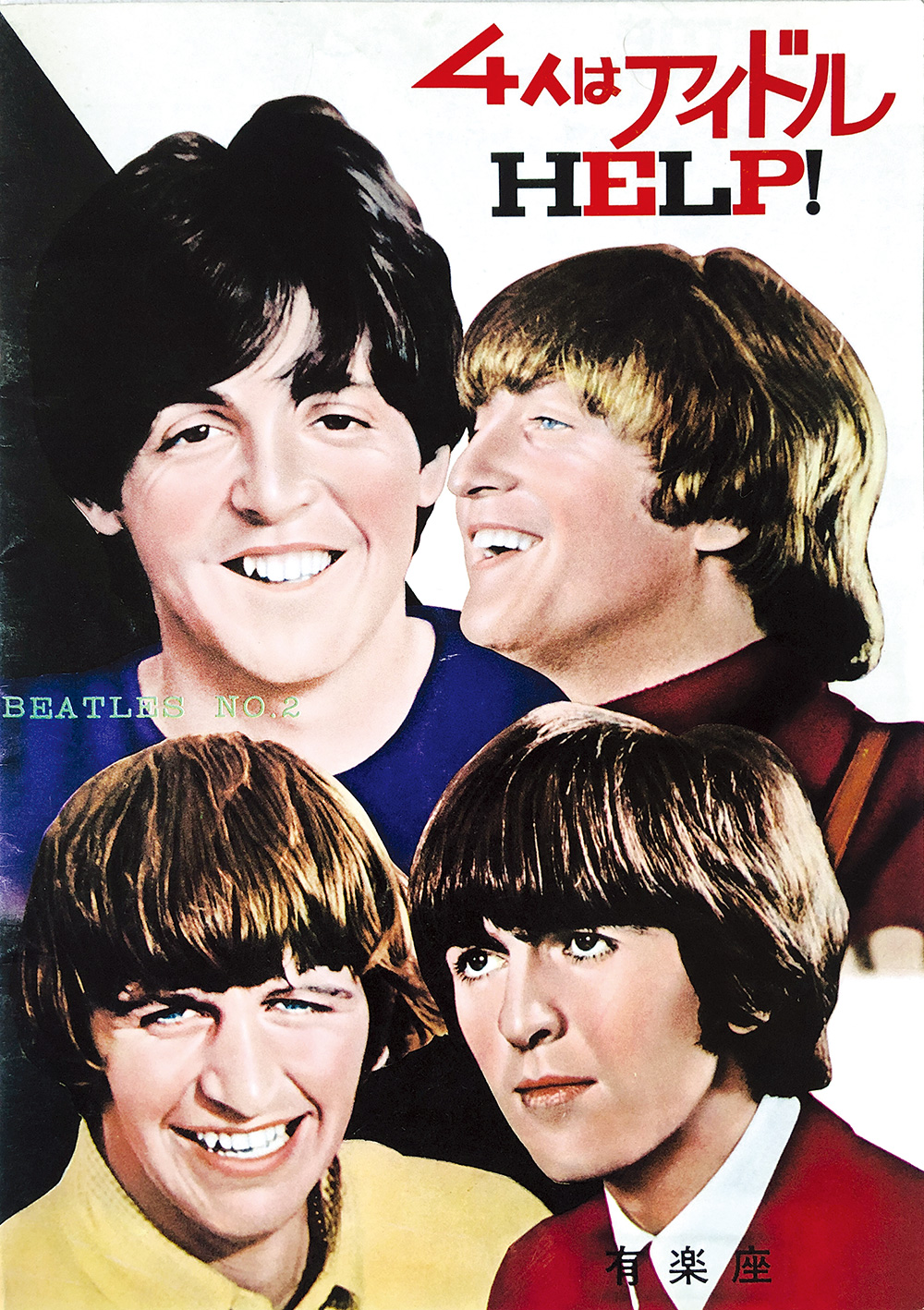

is one of their biggest fan bases in the world. Japan’s love affair with the Fab Four reached its peak 55 years ago, in the summer of 1966, when the band played five concerts in Tokyo during what would become their very last tour. The band’s first records in Japan were released in 1964, and by 1965 they were widely known in the country. In the beginning, the four scruffy Liverpudlians were mainly seen by the Japanese as idols (even their album Help! was released in Japan as Yonin wa aidoru or The Four Are Idols). In other words, their image and personalities were seen as the main reason for their success. However, a part of the media sometimes associated the band’s appearance and music with increased antisocial behaviour in Japanese society.

By 1966 the group had grown wary of touring, but there were places they still longed to visit. For some time, John Lennon and George Harrison had been developing a deep interest in Asian culture and religion, and they saw industrialised Japan as an interesting hybrid, somewhere in between the Eastern and Western worlds. Their manager Brian Epstein saw Japan as a promising market (at the time the band’s seventh largest in terms of sales) with the potential for growth. However, it was two men, Victor Lewis and Nagashima Tatsuji, rather than Epstein, who made the Japanese tour possible. Lewis was a theatrical agent and booking manager. He was considered a trustworthy member of the band’s entourage. Nagashima was the president of an artist booking agency. He had spent most of his childhood in New York and London, spoke fluent English, was familiar with English and American music, and had been managing local singers and bringing foreign artists to Japan for several years.

Lewis first contacted Nagashima on 18 March 1966. He said that the Beatles wanted to come to Japan. Nagashima was worried because the Beatles were extremely expensive, but he was assured that the band would not lose their Japanese partners’ money.

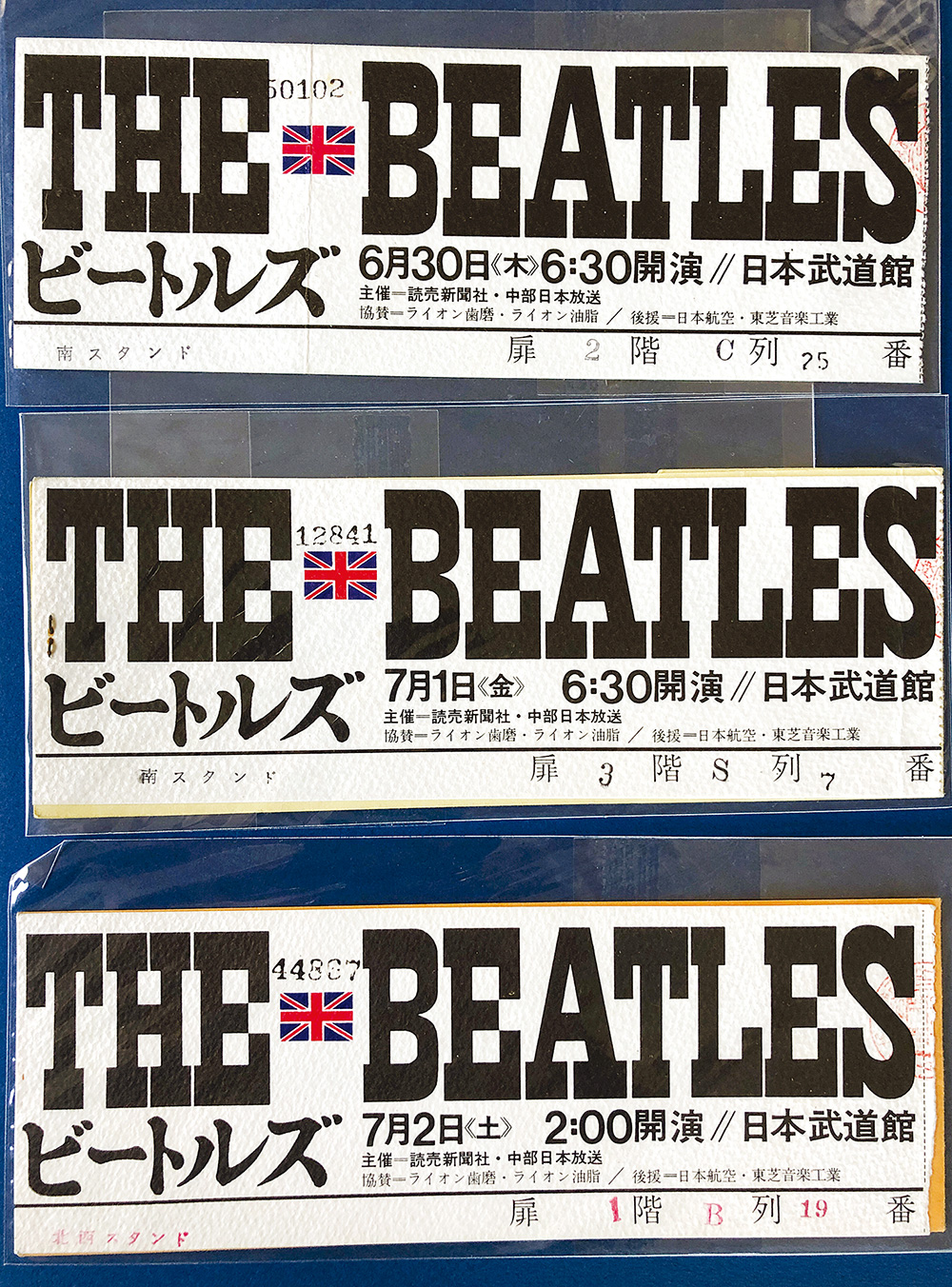

On 22 March, Nagashima flew to London and then New York to discuss appearance fees, the venue and ticket pricing with Epstein, and the contract was signed on 26 April. Though Nagashima thought that hardcore fans were prepared to pay as much as 10,000 yen (£65 / £265 in today’s money) for the premium tickets, they agreed to keep prices much lower: a bargain 2,100 yen for premium tickets, which happened to be the same price as a record album. Cheaper tickets cost 1,800 and 1,500 yen respectively.

Except for the Yomiuri Shimbun, one of Japan’s top newspapers, which was also one of the tour’s main sponsors, most mainstream media went to war with a frenzy of escalating headlines including Goo hoomu biitoruzu (Beatles, go home), Kutabare biitoruzu! (Drop dead, Beatles!) and Biitoruzu nanka koroshichae! (Kill the Beatles!). Regular TV commentators called them “crappy” and declared that “monkey-dancing to electric guitars is an impediment to human progress”. The Yomiuri Shimbun responded to these attacks by praising the band’s musical qualities and pointing out that in 1965 they had each been awarded the MBE (Member of the British Empire) by the Queen for their contribution to the arts.

By the time the band flew to Japan, Beatle mania (translated in Japan as biitoruzukyojidai or “the age of the Beatles’ craze”) was in full swing. A lot of fans wanted to see them live, but rigid social rules posed limits on when and how teenagers could attend a concert. For instance many high school students (particularly girls) could only go if accompanied by an adult, while in certain cities the schools had strict rules about extracurricular activities and forbade students attending.

The five concerts took place between 30 June and 2 July. Finding a big enough venue was a source of endless problems. Epstein insisted that he wanted a place with at least 10,000 seats, but outdoor venues such as stadiums could not be used as the Beatles would be performing during the rainy season.

The promoters thought they had found the ideal place in the Nippon Budokan, a new arena with a capacity of 14,000 that had been built for the 1964 Olympic Games. The problem was that the arena usually hosted martial arts competitions and, as such, it had acquired a semi-sacred status in the eyes of the conservatives and the famously violent right-wing groups. However, economic considerations all too often trump ideology, and on 26 May, the Budokan administrators gave their permission for the concerts.

Among the many issues that caused a headache for the Japanese, security was arguably the most pressing. The Tokyo Metropolitan Police created a special department to deal with the big event. All in all, the number of police on duty during the five days the Beatles spent in Tokyo was 8,370 – 3,000 of them were sent to Haneda Airport, 2,000 guarded the Tokyo Hilton Hotel and 2,200 were deployed at the Budokan.

A lot of time was spent discussing how to ensure audience safety. Most of the attendees would sit on balcony seats and everybody was worried that some of them would be so overcome they might fall over the barriers. It was agreed to install a two-metre trellis to prevent falls from the second-floor balcony. It was also stipulated that the lights should remain on throughout the concert. Most controversially, it was decided that the area right in front of the stage would not be used for seating, resulting in a spatial and emotional gap separating the musicians from their fans.

The band’s arrival was preceded by tropical storm Kit, a category 5 “super typhoon” that caused serious damage to the east coast of Honshu, the archipelago’s main island, and killed 64 people. Even the Beatles’ flight to Japan (JAL 412) was disrupted, finally reaching Tokyo at 3:40, more than 10 hours behind schedule. They came out of the plane wearing JAL branded happi coats over their suit jackets.

Apparently, a flight attendant called Satoko Condon convinced them to wear the traditional coats (that at the time were handed out to all first-class passengers) as a PR stunt. Then the foreign contingent was quickly whisked off to the cars that were waiting for them. Having entered Japan as “state guests,” they were able to skip all the paperwork at immigration and the customs officers didn’t even check their luggage.

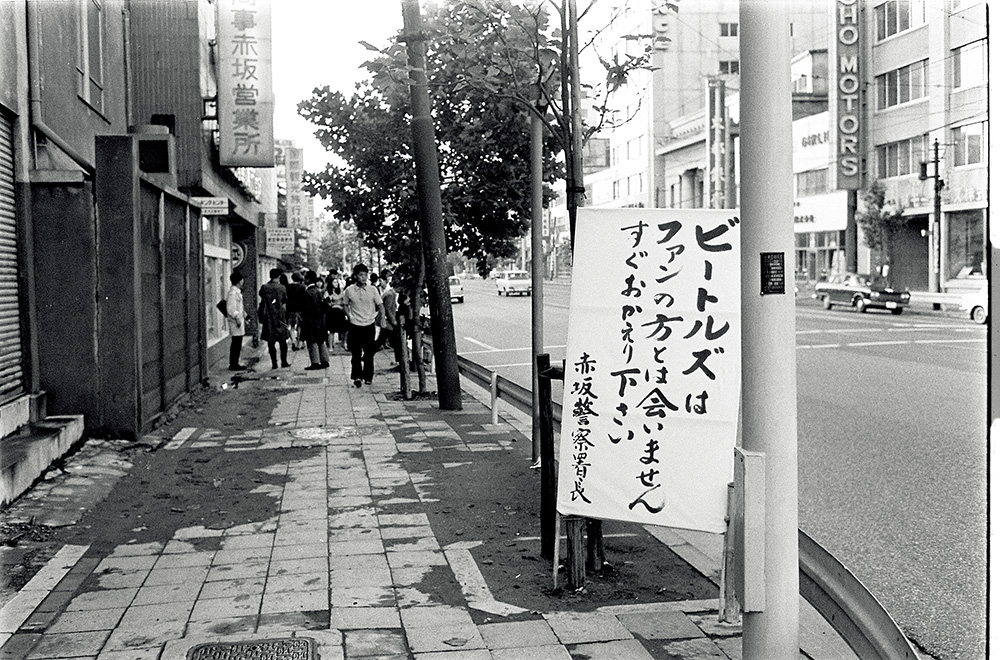

After a decade of battling left-wing students, the police had no problem handling the fans at the airport, while a contingent of right-wingers belonging to the Greater Japan Patriotic Society was intercepted on their way to Haneda where they planned to block the Beatles’ journey to Tokyo. In the meantime, other “patriots” (this time belonging to the Great Japan Patriotic Party) were protesting in front of the Tokyo Hilton, passing out flyers and putting up banners that read “Throw out the Beatles!”.

The band was given the Presidential Suite (Suite 1005) on the tenth floor. It was there that they ate meals via room service, received visitors (including a long parade of salesmen who tried to sell them goods), watched TV and painted. In the meantime, several hundred policemen were deployed to guard the hotel.

The Beatles’ first day in Japan was taken up with visits from British diplomats and Japanese VIPs and, chiefly, by a big press conference that attracted 216 reporters from 123 media corporations and around 70 photographers. The day after, on 30 June, they played their first concert, and to make sure the band would reach the Budokan – a 10-minute ride from the Hilton – without any problems, 1,700 regular and riot policemen were deployed and all the roads in between were blocked off.

The support acts began at 18:35. They included a few pop singers, two Group Sounds bands (the Blue Jeans and the Blue Comets) and even musical comedy group the Drifters.

The audience gave them a rather cold reception as they obviously only wanted to see the Beatles, who finally began their set at 19:35. Their new stage outfits, rather formal and subdued in colour, were probably an intentional choice as their management wanted to distance them from other wilder-looking rock bands.

The performance was judged as rather sloppy, which in retrospect seems to be somewhat harsh as there were extenuating circumstances, such as technical problems and the fact that their music was carried through the arena via the Budokan’s PA system, which was meant for announcements, not music, resulting in terrible sound quality. Be that as it may, the band finished its set after just 30 minutes, quickly bowed and left the stage without doing an encore.

As for the much-feared disturbance by fans, nothing really happened. Nobody left their seats (otherwise they would have been ejected immediately) and the girls in the arena spent the time waving their handkerchiefs and screaming. Only four fans received first aid for minor complaints such as headaches. The whole country must have breathed a sigh of relief.

The Beatles played twice on both 1 and 2 July – a matinee at 14:00 and an evening concert at 18:30 – and these performances went much better. In the end, depending on which source one refers to, a total of between 43,000 and 50,000 fans attended the five concerts. Between rehearsing and performing on stage, the four musicians took to painting. The tour organisers had provided them with a large piece of Japanese drawing paper and paints, and the four of them worked on it, bit by bit, each one decorating a corner of the sheet of paper. A white circle in the centre was left blank, and at the end it was filled with their signatures. When their “masterpiece” was completed, it was presented to the Japanese fan club president… who sold the painting in 1989 for 15 million yen. It later reappeared in 2002 on eBay, and in 2012 was sold by Philip Weiss Auctions for 155,250 dollars.

On 3 July, the band said goodbye to Japan. They left the Tokyo Hilton at 9:40 to catch their 10:40 flight (JAL 731), destination Manila. It seems that excessive security, threats, and technical issues notwithstanding, John, Paul, George and Ringo enjoyed their first visit to Japan quite a lot. Harrison later declared that “Japan was fantastic. A wonderful place, and wonderful people”, and devoted a good deal of his 1980 autobiography to this experience. Indeed, over the years, the Japanese have demonstrated that they are among some of the Beatles’ most loyal fans, ready to shell out tens of thousands of yen every time a former Beatle tours the country, and as the band’s entourage found out during their 1966 visit, they proved to be the most knowledgeable fans of all.

Gianni Simone