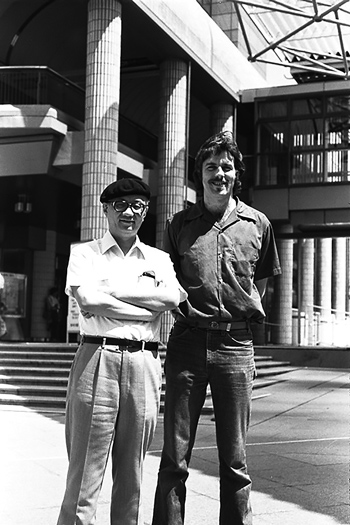

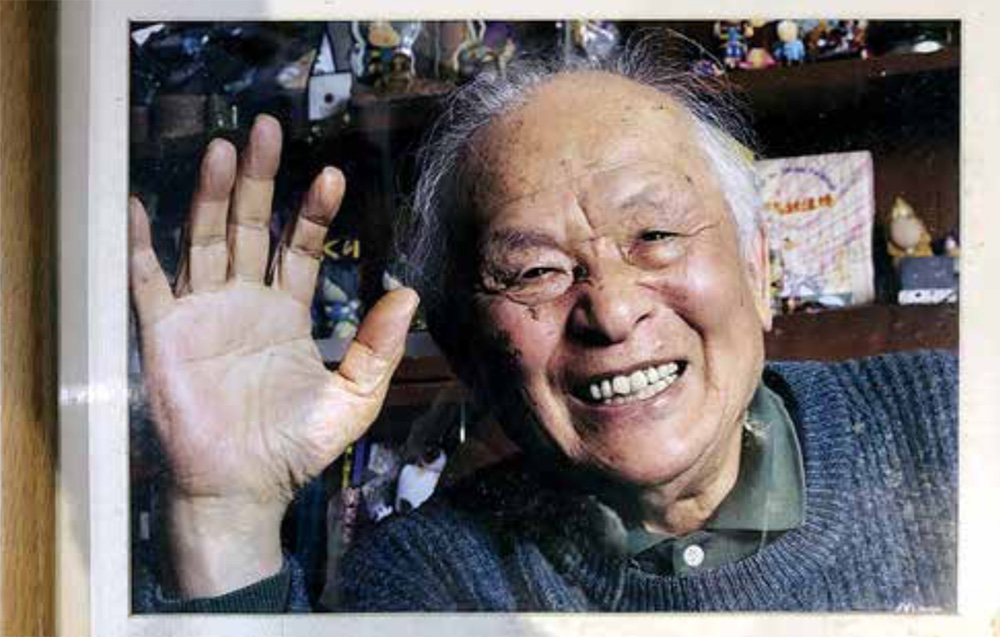

Haraguchi Naoko, the Mizuki Shigeru’s daughter, recalls her father and what life with him was like.

A lot has been written about Mizuki Shigeru’s art, but what was he like as a person and particularly as a family man? We asked his daughter, Haraguchi Naoko, who together with her husband, manages Mizuki’s work through their company, Mizuki Productions.

When you were born, your father was already in his forties, wasn’t he?

Haraguchi Naoko: Yes, that’s right.

As a child, how did you see your father?

H. N.: He was a very hardworking man. He worked at home, but he might as well have been somewhere else because we never saw him; he drew all the time, from morning till night. Dinner was the only time of the day the whole family spent together. I usually played with my sister who is four years younger than me. We sometimes sneaked into Dad’s studio and he let us stay if he wasn’t too busy. There were manga lying around everywhere, so we could spend hours reading them. At other times he would lose his patience and order us out. When I was a child and Dad was especially working on manga that were serialised in weekly magazines, he had an extremely tight schedule and couldn’t afford to take any time off, let alone play with us. Having said that, he certainly adored the whole family. I remember that every time we had Sports Day or School Visiting Day (when the parents had an opportunity to observe their children’s behaviour in class and the school environment), I would write a letter and leave it on his desk, hoping he would come to see me. He never did (laughs), but he kept all my letters.

It seems your father was an avid reader.

H. N.: Indeed, his studio was full of books and documents about his favourite subjects. He rarely read other people’s manga – he was too busy creating his own stories – but he had a lot of books on world folklore, from religion to dance and social customs. And of course, he had lots of books and documents about ghosts and yokai, and not only the Japanese kind. He had a great interest in world culture and visited several countries to research those subjects.

In a previous interview, Kamimura Kazuo’s daughter said that her mother didn’t really like her father’s job and lifestyle. What did your mother think about your father’s job?

H. N.: She didn’t dislike it. She may have been surprised by the kind of life he led when they married and came to live in Tokyo, and she realised how poor he was, but she saw he was a hardworking man with a real passion for his job, so she supported him as well as she could. She was always careful not to disturb him, and when he took a break she was always ready with a cup of tea.

One of Mizuki’s best-known works is a massive multi-volume history of the Showa period (1926-1989). You were born in the 1960s, in the middle of the economic boom. What was your father’s attitude towards that period in Japanese history?

H. N.: The postwar period in Japan was characterised by a huge drive to modernise the country and develop its industry. Science was all the rage, including research on atomic energy. This had the unfortunate side-effect of damaging the natural environment (e.g. due to air and water pollution) and disrupting the human connections that had been so important in the past. Tradition was seen as old-fashioned and was replaced with a new set of values. Dad didn’t like those changes at all. As someone who felt a strong connection with nature, he couldn’t approve of those practices. That’s why he created many comics and wrote essays affirming that mankind was part of the natural world and had a duty to love, respect and even fear it.

Growing up, what kind of relationship did you have with your father?

H. N.: When I was a child I really loved drawing and was good enough to earn my teacher’s praise. But my classmates would just say, of course she’s good: her father’s a comic artist. This kind of comment always drove me crazy. I wanted to be accepted for who I was. After all, I had drawn that picture, not my father. From that moment on, I tried to keep my identity secret [Mizuki was her father’s pen name, while she was known by their real surname, Mura]. Now, of course, I’m proud of my heritage and take every opportunity to talk about him and his art, but until I joined Mizuki Pro when I was in my mid-30s, I never volunteered this information, and only grudgingly revealed my father’s identity if someone asked me.

I read somewhere that you were even bullied for being Mizuki’s daughter.

H. N.: That’s my sister. She was made fun of because Dad was famous for drawing yokai. “You know yokai don’t exist?” she was told by another kid. “So your father is a liar!” She ran home from school crying.

Did you ever think about becoming a manga artist yourself ?

H. N.: The idea of working in manga or anime appealed to me, but I always worried about living in my father’s shadow. It’s hard to live up to expectations when your father is such a huge cultural icon. I actually helped my father for a short time. As you know, his drawings have so much detail. Well, he asked me to add all those tiny dots in the pictures, which is hard and tedious work. As you can imagine, I soon got bored and tired of it, at which point he came to the conclusion that I had no enthusiasm for manga and never asked me again.

If you have a real passion for the art, you should be willing to undertake even the most lowly of tasks, right?

H. N.: Exactly. When someone starts as an assistant, they have to handle such tasks as drawing frame borders and filling up spaces with black ink. Drawing dots, by the way, was one of my father’s assistants’ main tasks. It may look simple, but it’s not because you must have

a steady hand and those hundreds or thousands of dots must all look the same.

Speaking of assistants, even Tsuge Yoshiharu (see Zoom Japan no.68, Febraury 2019) worked for your father, didn’t he?

H. N.: Yes, he worked with Dad in the second half of the 1960s, though calling him an assistant would do him an injustice. After all, by the time he started helping Dad he was already a well-respected manga artist. He used to live not far from our house, above a ramen shop, and he often came to help. There were times when Dad ran out of good plot ideas and he’d ask Tsuge for suggestions. Also, Dad had problems drawing female characters, while Tsuge was famous for his cute girls, so he was always entrusted with drawing them. Another assistant who would become a famous artist was Ikegami Ryoichi. He came from Osaka and worked with us for almost two years before starting his solo career.

On average, how many assistants worked for your father at any given time?

H. N.: The peak was in the 1960s, when he was really busy and employed seven or eight assistants, but the average was probably more like five. He renovated and enlarged our house, adding more rooms and an attic, so the assistants could live with us. By the 1980s, when he decided to work less because it was affecting his health, they were down to two or three.

And did your mother look after everybody like in a sumo stable?

H. N.: No, it wasn’t like that. We shared the same kitchen and everyone did their own cooking. But when a deadline approached, everybody got incredibly busy, so my mother would cook for the whole staff. Most assistants were young single men who had moved to Tokyo and missed their families, so my mother’s food was very popular with them.

Your father was famous not only for his work but also for his original and unconventional way of life. Did you feel the same while he was alive?

H. N.: It’s hard to notice those things when you grow up with that person and see him every day. For you, whatever he does or says is just the norm. Even the fact that he was missing his left arm (he’d lost it during the war) was something I accepted matter-of-factly, even more so because he did everything without any help. The only thing he couldn’t do was cut his fingernails (laughs), so he’d ask my mother. Then, one day, when I was in junior high, we went out for a walk, and for the first time I noticed that people did a double take when they saw he only had one arm. That’s when I realised that being one-armed was anything but normal, and other people regarded it as something weird or scary. But Dad just didn’t mind. He didn’t care what others thought about him. He would even wear short-sleeved shirts without trying to hide the fact that he was missing an arm. Thinking back about his lifestyle and mind set, I see now that he was different. Japanese society encourages people to conform to non-written rules and common customs, and everybody tends to be- have the same in public, but my father carried on in his own way without caring how he was judged. He didn’t understand what was wrong with being different.

He was fundamentally a free spirit, wasn’t he?

H. N.: Yes, though, admittedly, there were times when he went too far, like when he was stopped by the police for riding a very old bicycle while only wearing what at first sight looked like underwear (laughs). He did his share of embarrassing things.

In pictures and video footage, your father looks like a very kind, laidback, happy-go-lucky person. However, I read that growing up in Sakaiminato he was considered a bully and a problem child.

H. N.: Indeed, at the time he was a typical gakidaisho (kids’ gang leader). On his first day of elementary school, he looked for the toughest-looking kid in his class and beat him up to make sure everybody understood who was the boss. He was big and strong and quickly became the leader of a gang of similar troublesome children. They often fought with other gangs to gain control of the area. They thought nothing of using sticks and throwing stones, and he often came home covered in blood. But he wasn’t just a selfish bully; he took care of his “soldiers” and didn’t try to rule by fear. That, at least, is what he used to say.

Mizuki Shigeru is famous for devoting his life to researching and drawing yokai (some 800 of them in Japan alone). Why do you think your father was so fascinated by yokai?

H. N.: While growing up in Sakaiminato, he met an old woman named Kageyama Fusa who sometimes worked at his home to help out. In Sakaiminato, there is a tendency to call people who serve the gods and Buddha Non-non- san, and she was the wife of a shaman, so people called her NonNonBa. She often took Dad to Shofuku-ji, a temple about 2 kilometres from his house, where there’s a map of hell on display in the main hall. It was such a powerful and frightening depiction of hell that it had a lasting impact on his impressionable mind. That picture and NonNonBa’s tall, scary tales revealed the existence of another world populated by spirits to my father.

Your father was also a philosopher of sorts.

He’s famous, among other things, for coming up with “Seven Rules to Be Happy”.

1. Don’t aim for success, honour or victory.

2. Keep doing the things you can’t help doing. 3. Pursue what you enjoy, don’t compare your- self to others.

4. Believe in your talent.

5. Be aware that talent and income are unrelated.

6. Be lazy.

7. Believe in the invisible world.

Why did he write them?

H. N.: It was mainly his editor’s idea, to express in a simple way the message he wanted to convey. His experience as a manga artist, for example, had taught him that even if you work hard and do what you believe in, you may not be successful, but that does not mean you should give up. Rule #2 is also very important. When as piring artists confessed to him they had doubts about continuing to draw manga and asked for his advice, he’d reply that you should become obsessed with what you’re doing to the point that you don’t care about other people’s opinions. My father endured many years of hardship before finally breaking through when he was already in his 40s, but he never gave up because he couldn’t help but draw.

Arguably the most famous of them is Rule #6: be lazy.

H. N.: Yes, and many people misunderstand its meaning. They think he was saying one should be idle in life, doing as little work as possible. However, what he really meant was that you should work like crazy when you’re young, so that when you’re older you can sit back and enjoy life at a slower pace because true happiness is not just about working hard. He’d learned this piece of wisdom from the Tolai, the inhabitants of Rabaul Island with whom he had become friends during the war. Indeed, when you look at the kind of life he led in the 1960s and early ’70s, he was anything but lazy. Probably because he found success relatively late in his life, he regarded manga editors like fuku no kami (gods of good fortune) and never refused an assignment for fear that if he turned them down they wouldn’t ask him again. Then when he was in his 50s he felt a pain in his chest and collapsed. At that point he realised he needed a break, and in the following years he only worked on projects he really liked. But he still, quite ironically, never put what he preached into practice. He was a workaholic at heart and kept drawing and giving interviews almost until the very end. He never succeeded in becoming lazy.

Interview by Gianni Simone