No less than 32 nationalities live in Ishinomaki. This presents a great opportunity if the city knows how to take advantage of it.

After the earthquake, the slogan “helping oneself” spread across Japan to encourage people to protect and look after their own safety and wellbeing. However, the idea of “helping others”, in particular vulnerable people with no means of protecting themselves, did not catch on and is still a problem in the region. Vulnerable groups obviously include the elderly, the disabled and children, but they also include pregnant women, as well as foreigners who can experience language difficulties and cultural misunderstandings that could put them at risk during an unexpected event, like the one that took place five years ago.

In January 2016 there were 924 foreign residents in Ishinomaki, from 32 different countries, such as China, the Philippines and South Korea. This number increases year on year, and it is important to create an environment that allows language difficulties to be overcome, in preparation for another possible catastrophe. Lianet heard the word “tsunami” for the first time in her life back in 2011.

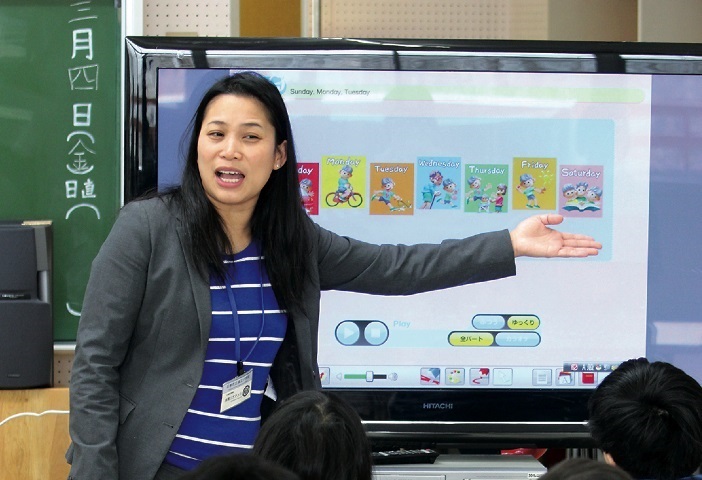

Originally from the Philippines and a Japanese resident for 23 years, Mrs Takahashi Lianet has now lived in Ishinomaki for 15 years, after getting married and having several children. Although she is fluent in Japanese and works as a language assistant in schools, she had no idea what the word “tsunami” meant until the earthquake took place on the 11th of March 2011. No less than 32 nationalities live in Ishinomaki. This presents a great opportunity if the city knows how to take advantage of it.

Immediately after the earthquake, she rushed to collect her children from nursery and primary school, taking no notice of her father-in-law who warned her of the danger. Luckily, the wave did not reach the schools, nor did it reach their house, and the whole family was safe and sound. She still finds it hard to imagine what could have happened if the tsunami had reached them.

Before the earthquake, Lianet had found it easy to adapt to life in Japan. She was a friendly, approachable person, easy to talk to, and often helped the elderly take out their rubbish. During the days that followed the earthquake, she went to the supermarket and a neighbour walked over to her and said, “Lianet, I know you have a baby. Here, I kept some milk for him”. She very much appreciated the gesture, which underlines for her how important communication is in everyday life.

Lianet considers herself to be “someone who moves forward,” and adds, with one of her characteristic smiles, that, “of course, I’m sad. But one must enjoy life to the full in the name of those who died”. Before the disaster, Ishinomaki had already set up an association, Kokusai Saakuru Yuko 21 (Circle of International Friendships 21), whose role was to foster cultural exchanges and offer Japanese language classes for foreigners.

Since 2015, another initiative has been set up, in order to support the city’s aim of helping people from different cultures to live alongside one another. “Japanese Juku” has been set in motion as a more general introduction to Japanese culture. Lianet is happy with this “favourable environment,” but wonders “how to develop more links between foreigners, between those who spontaneously take part in these activities, and those who don’t”.

During the earthquake she was surprised to see a considerable number of the Philippinos who live in Ishinomaki taking shelter in the city church. Her surprise reflected the weakness of the links between even close compatriots. Having become aware of the importance of these connections, after the earthquake, she hoped to create a place “where foreigners and Japanese could share more together – an opportunity for Japanese to learn about and understand foreign cultures”.

It’s now more important than ever to help foreigners who travel to Japan, including tourists. According to Lianet, notices relating to disaster prevention must be available in translation because “words such as “hinanjo” (evacuation centre) and “shienbusshi” (first-aid supplies) are hard for foreigners to understand”. Foreign nationals might find themselves in difficult situations during disasters because of their language and culture, but they could, on the other hand, become an important human resource to help promote disaster prevention among other foreigners.

Lianet speaks English, Japanese, Tagalog and Spanish. Should she be considered as being in a position of vulnerability in society? As the whole world watches the reconstruction of Ishonomaki, foreigners speaking several languages represent a useful resource for the region. Lianet also has another dream, that of “proudly making her second home better known in the world”.

Omi Shun

https://newsmediastand.com/nms/N0120.do?command=enter&mediaId=2301

Leave a Reply