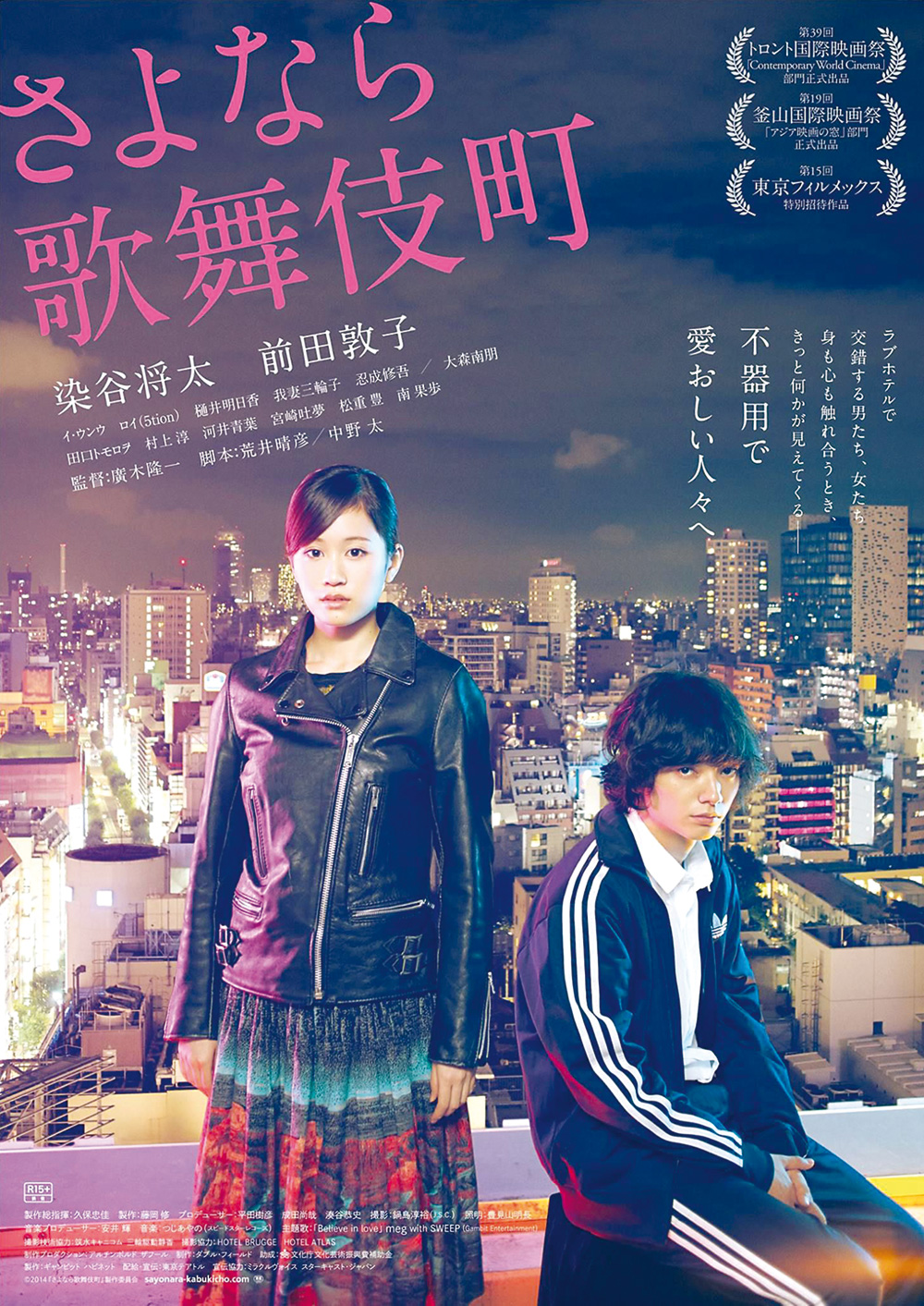

Made in 2014 by director HIROKI Ryuichi who began his career in pinku eiga (pink film), Kabukicho love hotel (Sayonara Kabukicho) takes place in a love hotel.

Made in 2014 by director HIROKI Ryuichi who began his career in pinku eiga (pink film), Kabukicho love hotel (Sayonara Kabukicho) takes place in a love hotel.

Since the end of the Second World War, the approach to sex in films has changed radically.

Sex and eroticism permeate every aspect of Japanese pop culture. Even putting aside its massive porn industry and the ever-popular hentai genre, these subjects have been amply covered by all media. Literature, films, manga and anime have explored sex in all its aspects, oscillating between titillation and the discussion of serious social issues. In this article, we are going to focus on postwar mainstream cinema. The postwar period started with a bang in 1946, when director SASAKIYasushi’sHatachi no seishun [Twenty-Year-Old Youth] hit the screens. The story itself is typical romantic stuff, and the film is certainly no masterpiece, but it features Japanese cinema’s first kiss, which made it into a major sensation at the time, so much so that 23rd May, its release date, was declared Kiss Day. Though the first on-screen kiss actually happened four months earlier, it went almost unnoticed because Ohitsu oharetsu [Pursuit] was only a short comedy film. Talking about his epoch-making scene, Hatachi no seishun’s male protagonist OSAKA Shiro later recalled that “kissing smelled of disinfectant”. This is because a small piece of gauze soaked with hydrogen peroxide had been sandwiched between the actors’ lips. Indeed, this was a different time, when even the act of kissing became the subject of public debate.

Interestingly, this particular kissing scene took place under the guidance of the Allied Occupation Forces. While the American authorities imposed strict censorship on anything that might remind the Japanese of their authoritarian, right-wing past, they used popular culture to promote a more liberal society. According to HIRANO Kyoko (author of Mr Smith Goes to Tokyo: Japanese Cinema Under the American Occupation, 1945- 1952), GHQ believed that, “it is essential for the Japanese to remodel their thoughts to openly express their desires and feelings in front of people without sneaking in love and affection”. At the same time, while the expression of desire was treated as liberating, explicit nudity was banned. Even the subject of “comfort women” (battlefront sex slaves) was forbidden as excessively erotic – thus contributing to the historical cover-up of this practice.

If wartime cinema was all about supporting the country’s military efforts, many postwar films were about the bad effect of the conflict on people’s lives. In 1948, even OzU Yasujiro contributed to this genre with Kaze no naka no mendori (A Hen in the Wind), the story of a young wife who is waiting for her husband to return from the front. When her son falls ill, she is forced to prostitute herself for a night to pay the high hospital bills. OzU’s story portrays Japanese society when the country did not yet have a universal health insurance system, and soldiers’ families were having a great deal of trouble making ends meet. While OzU never shows people in bed, this work stands out in his filmography for being the only title featuring high drama with a particularly violent scene in which the wife is pushed down the stairs by her husband.

Though TANAKA Kinuyo – the protagonist in OzU’s film – flies down the stairs, TAKAMINE Hideko climbs them again and again in NARUSE Mikio’s Onna ga kaidan o noboru toki (When a Woman Ascends the Stairs, 1960). In what is considered the culmination of NARUSE’s cinematic work devoted to women’s role in society, TAKAMINE plays Keiko, the middle-aged manager (or mamasan, as they are known in Japanese) of a hostess bar in Ginza. Respected by her colleagues and sought after by her clients, the widowed hostess is trying to open her own bar, but lacks the necessary money. Becoming a mistress of a rich man would be the quickest solution to her financial concerns, but that’s the last thing she’s ready to do.

The film title alludes to Keiko’s feelings towards her job and situation: she despises going up the stairs that lead to the bar each night because she’s all too aware that in her bar – and other such places – women are sexualised and become the object of men’s lust. At the same time, she knows that hostessing offers a woman one of the rare ways of becoming economically independent.

Eventually, even the faultless Keiko ends up in bed with a married customer to raise the money she needs to take care of her family. In the film’s final sequence, we see Keiko once again ascending the stairs, with a bright smile and a heavy heart.

NARUSE’s film came out at the end of the 1950s, a decade in which Japanese society went through a series of epochal changes and social struggles. As far as cinema and sexual mores are concerned, 1956 was an especially important year. For one thing, MIzOGUCHI Kenji released his final work, Akasen chitai or Red-light district, Street of shame, a sort of tragicomedy depicting the life of five women who work in a brothel in Yoshiwara [the Akasen chitai or Red-light district of the original title). Each one of them has different problems and motivations (one of them is supporting her young child and unemployed husband; another is planning to pay off her debt and leave the brothel), but MIzOGUCHI shows in even-handed, quasi-documentary style that their troubles are financial rather than moral.

Akasen chitai or Red-light district, Street of shame can also be seen as a sort of historical document because it was made while the Diet was debating a ban on prostitution. As a matter of fact, the Prostitution Prevention Law was enacted only a couple of months after the films’s release. MIzOGUCHIwas criticised at the time for his ambivalent attitude towards prostitution. This element is actually one of the best things about the film as the director depicts all sides of the problem, including the fact that not all sex workers are miserable.

If MIzOGUCHI represented the old guard of Japanese cinema, a couple of films that came out in the same year heralded new trends both in film-making and Japanese society. FURUKAWATakumi’s Taiyo no kisetsu (Season of the sun) and NAKAHIRA Ko’s Kurutta kajitsu (Crazed fruit) (both based on ISHIHARA Shintaro novels) exploded onto local screens on 17th May and 12th July respectively. The depicted (well, metaphorically speaking) a lot of casual sex and inaugurated the brief but frantic era of the “Sun Tribe” (Taiyo-zoku) generation, a group of privileged youth who spent their days drinking, sailing, and chasing girls. Seemingly oblivious to the country’s efforts to rebuild the economy after the war and the sacrifices it demanded from most people, the rich and dissolute youth ISHIHARA depicted were both criticised and envied for their reckless and carefree lives.

The “Sun Tribe” novels and films may just have been the creative expression of a small elite group CINEMA Nothing to get excited about Since the end of the Second World War, the approach to sex in films has changed radically. The first kiss in Japanese cinema, in 1946. Shôchiku February 2021 number 83 ZOOM JAPAN 15 CULTURE of rich brats, but the anger and violence presented in these stories could also be witnessed in the streets of Tokyo and other Japanese cities where people were demonstrating against the US-Japan Security Treaty. The same street protests are featured in Cruel Story of Youth, the 1960 film by OSHIMANagisa that announced the arrival of the Japanese New Wave.

In contrast to the privileged members of the “Sun Tribe”, the youth who appear in OSHIMA’s film are petty criminals and outsiders, but are motivated by the same animal instincts. Of course, there is plenty of sex (pretty tame by today’s standards, but not for filmgoers at the time), including a scene where a boy takes a girl he has just met on a motorboat ride on a river and rapes her… after which the couple falls in love.

The use of rape scenes is arguably one of the more disturbing features not only in Japanese cinema but in literature and manga as well, including mainstream works. Rape is not only often depicted casually, but the victim frequently ends up enjoying it and even falling in love with the rapist. The most famous example of this controversial trend is The Rapeman, a manga whose stories, surprisingly enough, were authored by a woman, AIzAKIKeiko. Published from 1985 to 1992, the series was adapted into nine live-action films between 1993 and 1996. The eponymous rapist is a nice, handsome high school teacher who also runs Rapeman Services, a business whose goal, as its classy motto says, is “Righting wrongs through penetration”. Clients include guys who have been dumped by their girlfriend or company employees who want to teach a “disruptive coworker” a lesson.

The popularity of these films is easier to understand when analysed against the backdrop of Japan’s misogynistic society, where even politicians and Cabinet members are caught blaming victims for being raped. Then again, even in the West there are people who don’t seem to have any problem with these films. For example, Thomas and Yuko Weisser, in their Japanese Cinema Encyclopedia: The Sex Films, wrote that NAGAISHITakao, who directed seven of the nine films, had taken “a patently offensive premise and twisted it into a wickedly funny black-comedy for adults… And, most importantly, he has taken the time to develop a group of characters who are actually very likeable”. Figure that one out. One of the things that sets Japanese cinema apart from other countries is that several directors cut their teeth in the “pink film” softcore porn genre before making the jump to mainstream movies. One such director is HIROKI Ryuichi who has continued to explore sexual themes throughout his career. Kabukicho love hotel (2014), for example, is an ensemble drama taking place in a love hotel (See pp. 20-23) in Kabukicho, arguably Tokyo’s sleaziest red-light district. One of the characters is a guy who, after losing his job at a five-star hotel, finds himself managing a love hotel and witnessing the disparate events and stories that unfold during a 24-hour period.

We could not end our brief excursion without including the most notorious title in the genre: OSHIMA Nagisa’s In the Realm of the Senses. Based on a real incident – the passionate, allconsuming love affair between ABE Sada, a former prostitute, and a restaurant owner, which culminated in ABE killing her lover by erotic asphyxiation and then cutting off his genitals. OSHIMA’s film is arguably one of cinema’s only erotic masterpieces; a rare mainstream work (mainstream meaning that it circulated in the commercial theatre network, not the porn market) that graphically shows long scenes of unsimulated sex.

Released in 1976, the film was first heavily cut by the censors before being seized by the authorities and becoming the subject of a long obscenity trial, which dragged on until 1978. By means of eloquent argumentation and thanks to wide public support, OSHIMA successfully forced the court to define obscenity, eventually winning the case.

In the end, In the Realm of the Senses is an extraordinary meditation on the physicality and emotional power of sex. The director once declared: “I believe that through union with another individual one is attempting union with all of humanity and all of nature.” The film shows this striving for such union.

GIANNI SIMONE