There’s been a growing movement in South Korea over the past few months to boycott Japanese products./All Rights Reserved

According to TASAkI Shin’ya, one of the best wine experts, Japanese wine production is remarkably characterful.

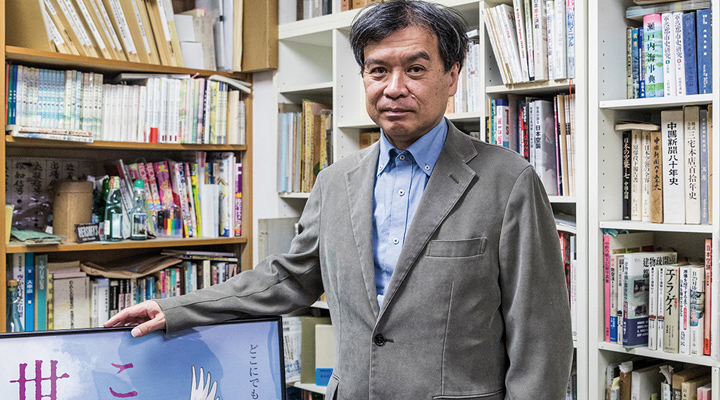

When talking about Japanese wine, few people are as knowledgeable as sommelier and all-round spirits and food expert TASAKI Shin’ya. A graduate from the French Academie du Vin (sommelier course), TASAKI won the third Japan Sommelier Contest in 1983 at the age of 25 and in 1995, he was recognised as the Best Sommelier in the World. Zoom Japan talked with TASAKI about the past, present and future of Japanese wine.

I heard that originally you wanted to become a chef. How did you end up becoming a sommelier instead?

TASAKI Shin’ya: Very simply, when I was 16 and decided I wanted to work in the catering industry, the job of sommelier wasn’t an established profession in Japan. You couldn’t even get a licence. In the early 1970s, the only available career was that of a chef. So I started working at a Japanese restaurant and then moved to a French one. There, I became fascinated with customer service. In traditional Japanese restaurants this is typically a female job; men cook food and women take care of the clients. But in French restaurants many men work as waiters too. So I switched to customer service, wanting to become a maitre d’. The problem was, at the time, I knew nothing about wine, I had never even tasted it. But in French restaurants, of course, most customers drink wine. So from the age of 19, I spent three years in France to learn everything I needed to know, and eventually graduated from sommelier school.

After returning to Japan, I won the national sommelier contest, and suddenly everybody wanted to talk to me about wine, particularly on how to better pair wine and Japanese food – something that was still quite unheard of at the time. So I finally decided to become a professional sommelier.

In Japan, wine is still not as popular as in France or italy, where it is consumed on a daily basis. What is the current image of wine in Japan?

T. S.: Of course, the local market is not as big as in Europe. One reason is that compared to other countries, Japan offers a wider choice of more traditional alcoholic beverages, from sake to beer and shochu, and people drink different spirits depending on the food or the season. At the same time, wine is not considered as exotic as it was until ten years ago. Most people have drunk wine at least once in their life, and many do it pretty regularly.

One interesting difference with France and Italy is that people there take wine for granted. Since childhood, they get accustomed to seeing a bottle of wine on the dining table. They drink wine because food paired with wine tastes better. It’s something they do without giving it too much thought. In Japan, on the other hand, people drink alcohol as a means to feel good – sometimes to the point of getting drunk – lose their inhibitions, and communicate more easily with other people. In many social situations, drinking is the main thing. You may nibble at a few snacks, but food and booze don’t necessarily go together in Japan. Many wine lovers, for example, go to a wine bar after having dinner, just for the sake of tasting some fine wine.

For many years, the Japanese only drank foreign wine. Has their appreciation of Japanese wine changed lately?

T. S.: It’s true that in the past the average quality of Japanese wine was not good enough to compete with France, Italy and other countries. Wine production in Japan dates back to the 1870s, but in those years it was a complete failure among the locals. In the following years, fortified wine (made with added brandy or another distilled spirit, or spices) became all the rage, and until the 1960s the Japanese only drank port and other sweet wines. In the 1970s, German wine became very popular. A lot of customers at smart French restaurants were doctors who had studied in Germany, so they tended to favour German wine. Another favourite was Mateus rose, a sweet sparkling wine from Portugal. Fast forward to the 90s when in 1994-95, a Japanese company began to import very cheap Spanish wine at 290 yen (£2) per bottle. Also, in 1997 there was a “polyphenol boom”, i.e. sales of red wine because of the health benefits of polyphenol present in it. So you could say that wine became really popular in Japan about 20-30 years ago.

How about Japanese wine?

T. S.: As I said, the first attempts at wine-making date back to the 19th century, but until the turn of this century local brands weren’t really taken into consideration when shopping for good wine. For many years, only table grapes were cultivated in Japan. Whenever those grapes were deemed not good enough for eating, or the harvest exceeded demand, they were diverted into wine production. As you can imagine, using table grapes is not a good recipe for making good wine. Things have changed in the last 20 years, partly after Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay became famous worldwide, and more wineries have appeared in several areas. More recently, there has also been a generational change that has helped the emergence of a different approach to wine making. In 2002, for example, I began collaboration with a winery in Nagano to make DOC-quality wine. The problem was that for too many years Japanese wineries were content with making a secondrate product for their local market. Predictably, the results were quite discouraging as 80% of the wine produced in the first year was terrible. Luckily, they have learned from their past mistakes, and in Nagano as in Yamanashi, Hokkaido and other prefectures they now make very good wine.

So i guess it’s become easier to introduce Japanese wine to your customers?

T. S.: They are definitely more open to local wine. In Tokyo’s Nihonbashi, for example, I collaborate with a restaurant that stocks 300 different wines from Yamanashi only. Also, I’m a consultant for a restaurant in Shinjuku that stocks 400 brands from around Japan.

Most wineries are concentrated in Yamanashi Prefecture (generally considered Japan’s prime wine area), Nagano, Hokkaido and Yamagata. What differences are there between them?

T. S.: The weather and climate are very different in each area, which obviously affects wine production. Also, the Japanese Alps in the middle of Honshu create a huge climate divide between western and eastern Japan. Hokkaido, for example, is different from the rest of the country because it has a much drier climate, and ongoing global warming is making that area even better for grape cultivation. Wineries are opening everywhere up north, and we can foresee a not so distant future when Hokkaido will become Japan’s best wine producer.

Nagano is another area that is being positively affected by higher average temperatures. Being a mountainous prefecture, in the past it was impossible to grow grapes at over 400 metres above sea-level. But now they are starting wineries at altitudes as high as 800 metres.

Yamanashi, on the contrary, is surrounded by mountains, and its annual rainfall is similar to Bordeaux. However, while in France it mainly rains in winter when grapes aren’t growing, in Yamanashi it rains a lot in June, August and September, and the basin-shaped region tends to get hotter through the summer. A common problem across Japan is that in the autumn, just when the grapes ripen, it rains a lot, and we even have a typhoon season, so humidity levels are very high. Generally speaking, making international-standard white wine in Japan is much easier than making red wine. A typical example of excellent Japanese white wine is Koshu, which has a light and soft flavour and goes very well with fish and Japanese cuisine.

Tokyo is not famous as a wine-making area, but i recently heard of a winery in the capital’s Nerima Ward.

T. S.: It’s a boutique winery that uses a variety of table grape called Takao, which grows in that area. There’s even a Fukagawa Winery in Koto Ward, believe it or not. Of course, there are no vineyards in Koto, so “winery” is a little bit misleading They just buy grapes from other places and make wine to be sold in their restaurant. Tokyo is full of surprises, even when it comes to wine-making, but both Nerima and Fukagawa are minor wines that can’t be compared to much better brands. Saitama Prefecture, just north of the capital, looks as though it might be an even more promising wine producing area than Tokyo. It’s a newcomer in the wine industry, but they have the right conditions to do great things.

In your opinion, what’s the best way to enjoy Japanese wine?

T. S.: As I said, because it rains a lot in Japan, local wines are quite fresh and light-flavoured. Something like Koshu white wine goes very well with Japanese food, particularly the kind of traditional cuisine that is served in restaurants. Tempura is also a nice pairing, and even sushi – not tuna, but white fish, salmon or Japanese scallops. Also, an interesting red wine that has recently been recognised internationally is made with a variety of grape from Niigata called Muscat Bailey A. It has a strawberry flavour and goes well with fish, pork and chicken cooked teriyaki style.

Do you think Japanese wine has a future as an internationally recognised wine?

T. S.: Last year, at long last, a new law was introduced that established stricter rules to define what can be called “Japanese wine” as opposed to “domestic wine”. This has been a big step forward in making Japanese wine more credible at international level. At the same time, more and more wineries are opening everywhere, and even the big companies are increasingly committed to selling the real thing. Now is a particularly good moment to spread the word about Japanese brands because the general trend among consumers, even abroad, is towards drinking light-flavoured wines, just like the ones that are made in Japan. Even at the G20, we only served local wine, and it was a great success.

INTERVIEW BY JEAN DEROME